“Are you ready?” Our pilot swivels his head, and I nod instantly. The helicopter lifts, then lurches forward. I watch as bulges of partially-submerged hippos and wandering elephants appear in the curves and islets of the Cubango River below. This has got to be the strangest way to visit an art gallery, especially as we head toward the ancient wonders of Tsodilo Hills in Botswana.

Helicoptering Into Tsodilo Hills, Botswana’s Ancient Heartland

I am flying to the Tsodilo Hills. Only 35km from the Okavango Delta, these hills encompass a 10km² site with over 4,500 indigenous paintings. Nicknamed the “Louvre of the Desert” for its remarkable density of rock art, it forms a sacred, open-air gallery. This rocky outcrop should be tourist kryptonite. Yet, it remains in the shadow of the Okavango and its luxury lodges, and even then, poor roads dissuade potential visitors. Helicopter Horizons has created a solution: flying guests to attend guided art tours.

From the chopper windows, the landscape is transforming before my eyes. In minutes, we’ve flown from hippo-dotted waterways to the sparsely vegetated fringes of the Kalahari Desert. And, abruptly, there they are: the colossal mounds of the “Mountains of the Gods.” The helicopter strains against mild crosswinds, navigates the southern slopes of a large hill, and gradually descends to the desert floor.

Read more like this: Western Sahara. Africa’s Last Colony

Walking the Sacred Hills

I duck and step onto the sand. Our transfer is already waiting, but, shaking hands with our guide and driver, it’s impossible not to peer back at the settled helicopter. Blades still spinning as their momentum dwindles, the backdrop is unreal. The main peaks are Male, Female, and Child. The entire site is sacred to the resident Hambukushu and San people, who are among the oldest continuous human cultures. Today’s destination is Female Hill. Particularly renowned for its density of artwork, I’ll be walking the Rhino Trail, which wraps around its base.

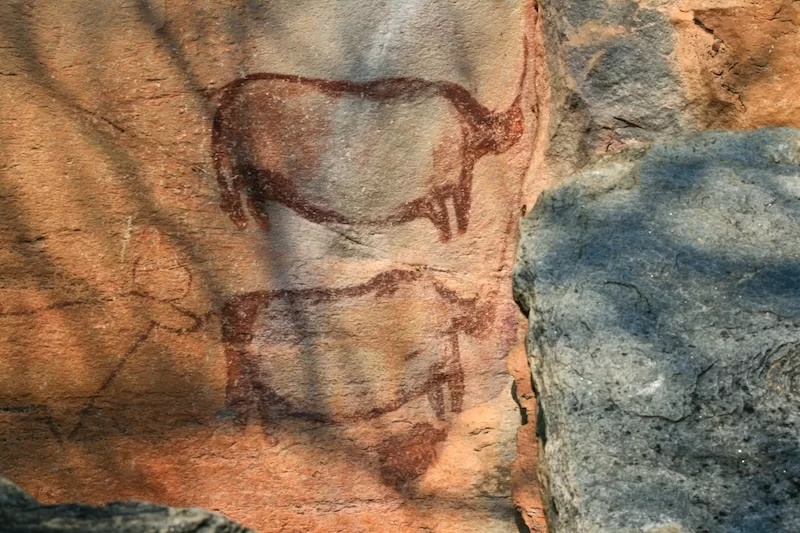

It’s a bumpy drive to the trailhead – something Tsodilo’s residents are campaigning to resolve in the hopes of increasing tourism. However, once we’re on foot, it’s smooth sailing. Padding along a soft sand trail, our guide points out the first depictions in seconds. The rocks themselves are beautiful, streaked with pink and orange stripes, and brightly leached with minerals. One by one, wild animals begin to emerge… giraffes, buffalo, and rhinos. All painstakingly etched in red. From a historical perspective, the color of these paintings matters. The Tsodilo Hills have been inhabited since the Stone Age, and housed two groups: the Ncaekhoe and the Bantu. The Ncaekhoe people used red paint to depict scenes of wild animals. The Bantu people led pastoralist lifestyles, arriving later and painting white artwork of domestic animals.

The contents of the paint are harder to ascertain than the artists’, but are believed to include animal fat, blood, urine, haematite, and charcoal. It seems miraculous that any of those ingredients would stay intact. “When it’s gone, it’s gone,” our guide nods, giving a wry smile, “We don’t renew.” As if by divine intervention, while some art has weathered away, those tucked under cliffside overhangs or caves remain clear as day.

Walking between surviving sections, our guide spots leopard tracks and explains the rituals of the San and Hambukushu communities, who continue to reside around the Tsodilo Hills. Hunting, water collecting – it all unravels around these rocks. There are historical tales, too. The creepiest is that of Sir Laurens van der Post, who has an entire slab of artwork named after him. The explorer and author didn’t seek permission from local chiefs before visiting, and after venturing around the base of Female Hill alone, his presence triggered a paranormal chain of events – culminating in him being unable to snap a photo of a particular rock. Laurens was eventually left terrified and fled to seek advice. He was told that he’d angered the mountains and was forced to bury a letter of forgiveness (which, legend has it, is still buried by the unphotographed painting).

Read more like this: The New Africa Travel List

As I was listening, my partner, Greg – never the effective multitasker – was attempting to photograph a distant depiction at Tsodilo Hills, Botswana. “Eibhlis,” he called, confused and slightly frustrated, “Can you take a picture of this rock?” He hadn’t been properly listening. But, lo and behold, his camera had spontaneously malfunctioned. He couldn’t snap a photo, no matter how many times he tried to click the shutter button. His face turned sheet white when we relayed the story.

Encounters With Tsodilo’s Spiritual Legacy

There were other moments where you felt the gravity of the spirituality behind the site. Reaching a cliffside with zero paintings, our guide pauses: “I have an assignment for you.” Glancing at me sideways, he asks me to spot something. Scanning the empty cliff-face, I throw a few guesses around, but none stick. Eventually, he reveals the answer: a rock in the shape of Africa. It wasn’t until we’d looped all the way back to the trailhead and reached the museum that I realized the importance of his phrasing. One exhibit read:

“The Hambukushu have a lot of respect for Tsodilo. If you send someone to Tsodilo and he or she undertakes the assignment unwillingly, chances are that they might not come back. To come back safely from Tsodilo, you are expected to accept the assigned tasks readily and to observe and respect the sacredness of Tsodilo.”

Where History Holds Its Ground

There is a weight that comes with visiting the Tsodilo Hills in Botswana. In 2026, the site celebrates 25 years of UNESCO status. It also marks 20 years since the San people won their court case against the Botswana government, a decision that ruled that they’d been illegally evicted from their ancestral lands. Yet, Tsodilo Hills, at the heart of indigenous spirituality, continues to be overlooked.

Clambering back into the helicopter, we rise up, hovering at eye-level with the summit of Female Hill in the Tsodilo Hills, Botswana. It might not be a glass pyramid; the site forgoes bright lights, noisy air conditioning, and obtuse descriptions under frames. However, Botswana’s “Louvre” demands a different type of engagement. It almost sends a shiver down my spine: I won’t look at four-walled galleries the same way again.

Read more like this: The Most Underrated Countries to Visit

Key Takeaways

What Makes Tsodilo Hills a UNESCO World Heritage Site?

Tsodilo Hills, located just 35 kilometers from the Okavango Delta in Botswana, is a 10-square-kilometer site encompassing over 4,500 indigenous rock paintings. Nicknamed the “Louvre of the Desert” for its remarkable density of rock art, Tsodilo was designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2001 (celebrating 25 years of UNESCO status in 2026). The site’s significance lies in its extraordinary concentration of ancient paintings created by the Ncaekhoe and Bantu peoples, representing continuous human cultural expression from the Stone Age to the present day. The paintings depict wild animals (created with red paint by the Ncaekhoe) and domestic animals (created with white paint by the Bantu), providing a visual record of cultural evolution and artistic techniques. The site remains sacred to the resident Hambukushu and San people, who continue to use the hills for hunting, water collection, and spiritual rituals.

How Do You Visit Tsodilo Hills and What’s the Helicopter Tour Experience Like?

The most accessible way to visit Tsodilo Hills is via helicopter tour operated by companies like Helicopter Horizons. The helicopter experience begins with an aerial perspective of the Okavango Delta’s hippo-dotted waterways and wandering elephants, providing a unique introduction to Botswana’s wildlife. The helicopter then flies over the sparsely vegetated fringes of the Kalahari Desert before landing on the desert floor near the “Mountains of the Gods”—the three main peaks known as Male, Female, and Child. From the landing site, visitors transfer to a guide-led walking tour, typically the Rhino Trail around Female Hill, which features the highest density of rock art. The entire experience combines aerial adventure, guided cultural interpretation, and intimate engagement with ancient art. Poor road conditions to the site make the helicopter approach particularly appealing for visitors seeking accessibility and a unique perspective unavailable through standard ground-based tourism.

What’s the Spiritual Significance of Tsodilo Hills and Why Is It Sacred?

Tsodilo Hills holds profound spiritual significance for the Hambukushu and San peoples, who consider the site sacred and continue to use it for hunting, water collection, and spiritual rituals. The spiritual weight of the site is palpable to visitors—the landscape itself seems to demand respect and reverence. Local guides explain that visitors are given “assignments” during their visit, and according to Hambukushu tradition, accepting these assignments willingly is essential for safe passage. The article includes a cautionary tale about explorer Sir Laurens van der Post, who visited without permission and allegedly angered the mountains, resulting in paranormal events and his inability to photograph certain rock art. The spiritual legacy extends to the present day, with visitors reporting unexplained camera malfunctions and other phenomena. The site’s sacredness is not merely historical or cultural—it’s a living spiritual force that continues to influence the experience of those who visit. The museum exhibit reinforces this: “The Hambukushu have a lot of respect for Tsodilo. If you send someone to Tsodilo and he or she undertakes the assignment unwillingly, chances are that they might not come back. To come back safely from Tsodilo, you are expected to accept the assigned

What Do the Rock Paintings at Tsodilo Reveal About Ancient African Cultures?

The rock paintings at Tsodilo Hills provide a visual record of cultural evolution spanning from the Stone Age to the present day. The paintings were created by two distinct peoples with different artistic traditions: the Ncaekhoe people used red paint (derived from haematite, animal fat, blood, and urine) to depict wild animals including giraffes, buffalo, and rhinos. The Bantu people, who arrived later and practiced pastoralism, used white paint to depict domestic animals. This distinction reveals not just artistic preference but fundamental differences in lifestyle and cultural practices. The paintings are remarkably preserved in some locations—particularly those tucked under cliffside overhangs or caves—while others have weathered away over millennia. The site’s guide emphasizes the fragility of these works: “When it’s gone, it’s gone. We don’t renew.” The rock art at Tsodilo represents one of Africa’s most significant cultural heritage sites, offering insights into indigenous artistic techniques, cultural practices, spiritual beliefs, and the continuous human presence in southern Africa. The paintings demonstrate sophisticated understanding of animal anatomy, composition, and artistic expression that challenges stereotypes about “primitive” African cultures.

What Are the Legal and Cultural Issues Surrounding Tsodilo Hills and Indigenous Rights?

Tsodilo Hills sits at the intersection of cultural preservation, indigenous rights, and tourism development in Africa. In 2006—20 years before the article’s publication—the San people won a landmark court case against the Botswana government, ruling that they had been illegally evicted from their ancestral lands. This legal victory was significant for indigenous rights across Africa, yet Tsodilo Hills, at the heart of indigenous spirituality and cultural heritage, remains overlooked in global tourism discourse. The site’s 25-year UNESCO status (as of 2026) has not translated into the international recognition or tourism infrastructure that comparable sites receive. The Hambukushu and San peoples continue to reside around Tsodilo Hills, maintaining their traditional practices of hunting and water collection, yet their voices and perspectives are often marginalized in tourism narratives. The poor road conditions to the site, while creating challenges for visitors, also reflect limited investment in tourism infrastructure despite the site’s UNESCO designation. This disparity between cultural significance and global recognition raises important questions about how indigenous heritage is valued, preserved, and presented to the world. The article’s emphasis on respecting the site’s sacredness and accepting the spiritual assignments offered by local guides is a subtle but important acknowledgment of indigenous authority and knowledge systems.

About the Author

Eibhlis Gale-Coleman is a travel writer from the UK. She has an ever-growing bucket list of “everywhere” and took her first solo trip abroad at 16 to volunteer in marine conservation.

Contact Author

"*" indicates required fields

Stay Ahead on Every Adventure!

Stay updated with the World News on Escape Artist. Get all the travel news, international destinations, expat living, moving abroad, Lifestyle Tips, and digital nomad opportunities. Your next journey starts here—don’t miss a moment! Subscribe Now!