Rain is pattering the windows; hardening splashes that threaten a tropical downpour. Sliding open the balcony door, I peer onto the white-and-yellow storefronts below: vendors are already sheltering in doorways. It’s a surprisingly sleepy start to a morning in Stone Town, Zanzibar.

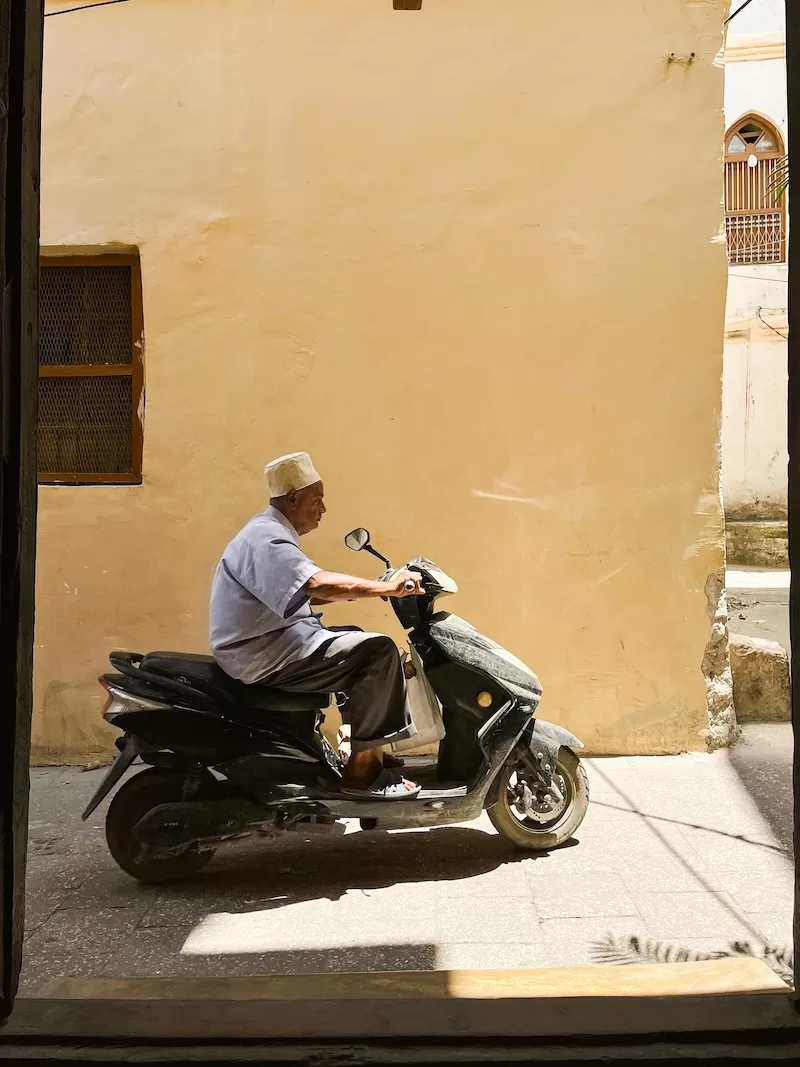

The island of Zanzibar, famed for its spices and trading history, sits 35 km off the Tanzanian coastline. Its capital, Stone Town, is a network of alleyways, markets, and minarets—snatching tourists on whistle-stop guided tours before they continue on clockwork transfers to manicured beach resorts. Given the quiet scenes outside my window, it seems the daily dance of parachute tourism is delayed. Clearly, the day is still whirring into action.

As a “detour destination,” Stone Town’s credentials speak for themselves. The city is UNESCO-recognized for its architecture, and centuries of trading have interjected Indian, Arabic, European, and Swahili influences. Stories lurk in plain sight, from forgotten carvings on residential doors to plastic spice packets sitting quietly on sidewalk stalls. Stone Town has merged into a living, breathing jigsaw of cultures.

Today, I’m taking a guided tour to understand its scattered pieces. Judging by the weather, I might need an umbrella.

A Story That Starts With Freddie Mercury?

I’m staying at the Freddie Mercury Apartments, emerging—ruffled hair—from a four-poster bed covered with plush red embroidery. This accommodation adjoins the Freddie Mercury Museum and has a bold claim to fame: it formerly housed the late Queen singer.

Mercury was born and raised in Stone Town, only fleeing to England at eight years old in 1964 to escape the Zanzibar Revolution. His Zanzibarian legacy is posthumously celebrated, despite his family’s hasty departure.

This conflict didn’t spring from thin air. The island’s earliest documented immigrants were African, with Persian travelers following shortly afterward, forming an African-Persian community around the 10th century. In the 15th century, the Portuguese arrived, controlling the island until Oman seized its shores two centuries later.

This final switch of occupiers had the largest impact. Omani traders sought their fortunes through slavery and spices, transforming Zanzibar into a plantation island. These industries would keep the island and its residents in a deadly grip throughout the 18th and early 19th centuries. As people were enslaved, displaced, and abused, ethics in Zanzibar were hotly debated on the international stage.

Omani power was quelled in 1890 by a British protectorate. In 1963, the Sultanate briefly regained independence, but Sultan Ḥamud ibn Moḥammed barely had time to warm his seat. In January 1964, a revolt overthrew the Sultanate and established the Republic of Tanzania.

This revolt drew a final line under the island’s complex history. As Freddie Mercury packed his bags in 1964, Zanzibar was resettling in the dust.

The Tour Begins

I don’t have long to walk. Freddie Mercury’s Apartments are located in Shangani, a coastal neighborhood in Stone Town. At the nearby Forodhani waterfront park, I meet my guide for today: Abdul.

Armed with a thick wad of laminated documents, Abdul is a hive of historical facts and immeasurable knowledge of Zanzibar. He immediately leads me toward the Old Fort, a 17th-century stronghold constructed during the Portuguese occupation. Standing in its stone-arched corridors, he explains that while the fortress is among the oldest buildings in Stone Town, its days as a military barracks are long gone. Now, Old Fort is a cherished venue for festivals and cultural celebrations. It’s strange to imagine the shape-shifting it has undergone over the centuries.

Following Abdul into the heart of the city, we leave Shangani and its Old Fort behind. Zigzagging through the thickened stone web of Stone Town’s alleyways, it feels like entering a maze. I’d purchased an umbrella, but with knee-deep “rivers” rushing through the narrow streets and black overhead wires swinging precariously above my head, it now seems a little redundant.

Abdul leads decisively ahead, already knowing which streets flash floods will have blocked entirely.

Lesson 1: Not Every House Is the Same

Jumping onto a stone doorstep, Abdul explains lesson number one: in Zanzibarian architecture, history is hidden in its houses.

“The Arabs in Zanzibar liked their privacy,” he laughs. Behind him is a plain-looking house with shuttered windows and white walls. It looks simple—boring, even. “Look here, though.” Abdul ushers me through an open doorway, which, to my surprise, turns out to be the entrance to a hotel lobby. Just as I’m questioning the likelihood of someone yelling “trespass,” the room opens into a beautiful inner courtyard. Plain exteriors, elaborate interiors—it’s a perfect demonstration of traditional Arabic architecture.

Stepping back onto flooded pavement, the Indian influence is easier to spot. Abdul waves at brightly colored houses with elaborate verandas and curved carvings. This architecture struts like a peacock at street level, its exteriors fronted by heavy wooden doors with the distinctive grids of Gujarat style. Zanzibar’s Indian architecture shrugs off any concept of modesty; curbside appeal was clearly the goal.

The density of architectural styles is staggering. Within minutes, Abdul also points out single-story Swahili houses, and bizarrely, a Gothic spire rises above the rooftops. Christ Church Cathedral is a total anomaly, its European architecture so convincing it could have been lifted straight from the streets of London.

Lesson 2: Zanzibar Might Be an Island, but It Embraces Politics

Amid our architectural “window shopping,” we arrive at Stone Town’s famous meeting point, Jaw’s Corner. This landmark is a hub of social connection—somewhere to drink coffee, play games, and discuss current affairs. The tradition began with regular screenings of the film Jaws on a tiny television, a backstory now immortalized in a sprawling shark mural.

As we approach, Abdul stops me. “You’ll have seen the banners of the main party,” he explains, “but here—these are the colors of the opposition.” The flag-stoned square is a fluttering display of purple, not green. Its demographic predominantly consists of men aged 60 to 70, who glance briefly at us before returning to their espresso. Zanzibar might be a dreamy beach destination, but the intensity of political opinion thickens the air at Jaw’s Corner.

Lesson 3: Spice Trading Is Alive and Well

With little to contribute to political debate, we move on to Darajani Market—the beating heart of Stone Town’s trading legacy. Also referred to as the “souk” or “bazaar” (Arabic and Persian for “market”), “Darajani” means “bridge” in Swahili, a fitting name given that a river once ran nearby.

Originally constructed in 1904, the market has spilled into surrounding streets. Ducking under dangling fruit, I hop across puddles of mud-brown water. The market predominantly sells food, though Abdul assures me technology stalls lurk somewhere. We breeze through the seafood section (who knew dried octopus retained such a pungent smell) and head straight for the spice stalls.

Everyone is bartering. Middle-aged women clutch bulging plastic bags, vendors peer from behind maximalist displays, and teenagers call after us with offers of samples. Abdul cuts through the chaos to his friend’s stall. The trader patiently helps me identify cardamom, cinnamon, nutmeg, and vividly colored curry blends. It’s fascinating to see spice trading still thriving.

Lesson 4: Zanzibar’s Slave History Is Never Far Away

At Darajani Market, the trader hands me stiffened dark-brown flower buds. Stone Town has a habit of slipping poignant clues under your nose. These fragments are Zanzibar’s most historic spice: cloves.

Throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, Zanzibar became the largest slave-trading center in East Africa, its plantations powered by enslaved labor. Under Omani rule, cloves were grown, picked, and packaged by slaves. It’s hard to reconcile such heavy history with something so small.

Our final stop is the East Africa Slave Trade Exhibition. Inside the repurposed halls of a cathedral, I read floor-to-ceiling accounts of brutality: abductions on the mainland, plantation labor, and dehumanizing export markets.

Abdul leads me below the church to a set of uneven stone steps. Two low-ceilinged chambers emerge. At 5’3″, I stoop slightly, shining my phone’s light inside. As many as 75 prisoners would have been crammed into these rooms.

By 1873, the slave trade was banned—though enforcement lagged until 1897. With millions displaced, the generational damage is irreversible. This history is etched into the stone of Stone Town.

Takeaway: Stone Town Deserves More Than a Day

When I step outside, the rain has stopped. The sun burns away the last puddles. Without flooded streets or a clutched umbrella, the walk back to Shangani feels transformed.

The city is awake now. I follow Abdul along newly accessible routes, stopping at the Hamam Persian Baths and testing my ability to identify Arab versus Indian architecture. At Forodhani waterfront park, we say goodbye, and I walk alone.

Have I pieced together the jigsaw? Partly. Stone Town wears its story openly, if you know where to look. But while Abdul helped me memorize the pieces in a morning, understanding their meaning takes time.

I’ve scheduled two days here, and that feels like the bare minimum. From cloves to espresso at Jaw’s Corner, Stone Town resists easy answers. This cultural jigsaw needs far longer than a whistle-stop tour.

About the Author

Eibhlis Gale-Coleman is a travel writer from the UK. She has an ever-growing bucket list of “everywhere” and took her first solo trip abroad at 16 to volunteer in marine conservation.

Contact Author

"*" indicates required fields

Stay Ahead on Every Adventure!

Stay updated with the World News on Escape Artist. Get all the travel news, international destinations, expat living, moving abroad, Lifestyle Tips, and digital nomad opportunities. Your next journey starts here—don’t miss a moment! Subscribe Now!