A New Wales in the New World

Picture this: you’re in a cottage, tucking into a plate of Bara Brith with a cup of tea. The sound of Christian hymns drifts faintly from a chapel down the road. A chill moves through the house as you pull your cardigan tighter against the cold. You could be somewhere in Carmarthenshire or up in the Valleys—until you glance outside and see towering mountains, glacial lakes, and wild rivers.

However, this isn’t Wales at all, but in the villages of Patagonia, in the heart of Argentina, where the Welsh language and culture have endured for more than 150 years. For expats or long-term travelers in Argentina, stepping into Welsh Patagonia can feel like finding a fragment of home—an unexpected reminder that language and community can survive even far from their roots.

Origins of a Dream

In the mid-nineteenth century, many Welsh speakers feared that their language and culture were being eroded by the growing tide of Anglicization, accelerated by the Industrial Revolution. These fears were confirmed by the release of the Blue Books in 1847—a report commissioned by the British government to assess the Welsh education system but which turned into a thinly veiled attack on Welsh life and identity.

The report portrayed the Welsh as backward and in need of further Anglicization. Its most damaging suggestion was that the Welsh language itself should be stamped out. In response, a group of Welsh-speaking Christians, led by Michael D. Jones, began to dream of a settlement abroad—a place where they could live, worship, and educate their children in Welsh, free from English interference.

In 1865, around 150 settlers sailed from Liverpool and arrived in Argentina’s Chubut Province. The land was not the lush farmland they had been promised but a dry, harsh plain with unforgiving weather. Survival was difficult; food was scarce, and shelter was minimal.

Over time, however, the settlers built a life. They dug canals that transformed the valley into fertile farmland, enabling crops to grow. As the settlement prospered, the Argentine government—pleased by their industry and order—granted them official title to the land in 1875.

Read more like this: Living in Argentina

Welsh Patagonia’s Culture and Language Today

The descendants of those first settlers still live in the Chubut Valley today. Towns across the region bear distinctly Welsh names—Trelew, Gaiman, Rawson, and Trevelin—and together they form what is known as Welsh Patagonia, or Y Wladfa.

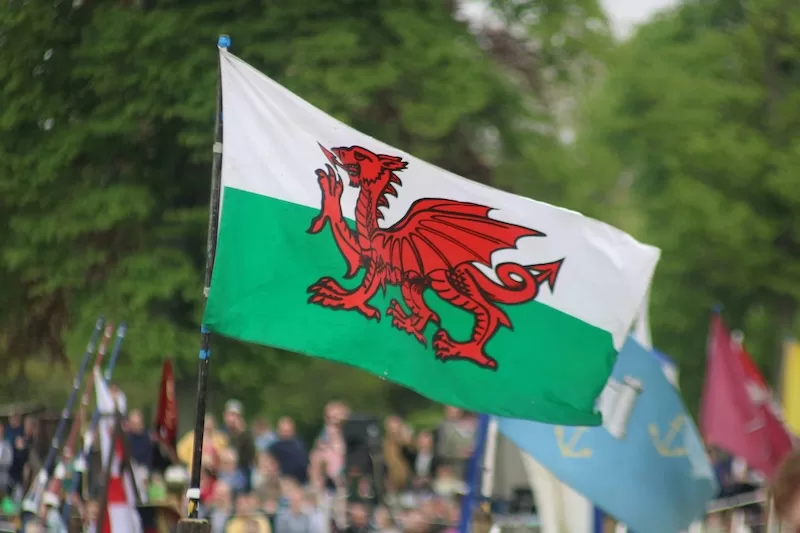

The Welsh language is still spoken by several thousand people here, and efforts to keep it alive remain strong. Though Spanish now dominates daily life, Welsh is taught in local schools, sung in chapels, and celebrated in community gatherings. Welsh teachers from Wales are regularly sent on placement to Patagonia, while scholarships allow Patagonian students to study in Welsh universities.

Street signs are bilingual, and Welsh Patagonia’s traditional festivals, such as Eisteddfod, remain major annual celebrations. Visitors often find themselves learning a few Welsh phrases just to take part in community life.

The tea houses of Gaiman and Trevelin are another enduring tradition—places where cakes, breads, and tea are served in the old style, often alongside photographs and artifacts of the first settlers.

Modern Life and Challenges

Welsh Patagonia, like the rest of Argentina, continues to modernize, yet there are conscious efforts to preserve its heritage. Spanish is now the dominant language, but many families still speak Welsh at home, and younger generations are often bilingual. Maintaining a minority language so far from its homeland is no easy task, but support from the Welsh government and local initiatives ensure that Welsh remains a living part of daily life.

The region is remote, relying mainly on agriculture and tourism. Towns are small and widely spaced, and public services are limited compared to Argentina’s larger cities. Yet this isolation may be the very reason Welsh culture has survived here for so long—the land has protected its traditions as fiercely as its people have.

For expats, life in Welsh Patagonia is defined by that remoteness. Long distances between towns, reliance on agriculture, and the rhythms of rural life shape a slower, more grounded way of living.

Still, the region’s history is complex. While the Welsh settlers came to escape cultural oppression, the land they occupied was originally home to the Indigenous Tehuelche people, who were displaced. The Welsh colonization of Patagonia—though born from a struggle for survival—was also part of a broader Argentine expansion into Indigenous territory, a history still being reckoned with today.

Read more like this: Great Places to Live in South America

Visiting the Welsh Patagonia Region

Reaching Welsh Patagonia requires intention. The region is vast and sparsely populated. Most visitors fly into Trelew from Buenos Aires, then travel between towns by bus or hire a car.

Beyond its cultural intrigue, Patagonia itself offers breathtaking natural beauty—mountains, glacial lakes, and open valleys that attract hikers and adventurers from around the world.

Gaiman is often considered the most authentically Welsh town. With a population of around 6,000, it’s home to chapels that still hold Welsh-language services and tea houses that feel unchanged since the nineteenth century.

Visitors often come during Eisteddfod in summer or Gwyl y Glaniad in July, which marks the anniversary of the settlers’ arrival.

Why Welsh Culture Endures Here

The story of Welsh Patagonia is more than a historical curiosity—it’s a testament to cultural resilience. The Welsh, Irish, and Scots all saw their native languages threatened by Anglicization. Today, Irish and Scottish Gaelic are considered endangered, while Welsh is held up as a model for revival—not only thriving in Wales but also, remarkably, in Argentina.

Despite the passing of time and the distance from home, the people of Welsh Patagonia have maintained a living culture that is neither entirely Welsh nor entirely Argentine. It’s something in between—a hybrid identity that has evolved through adaptation rather than nostalgia.

For those who live here, Welsh Patagonia is not a museum of the past but a community that continues to grow, change, and endure. It stands as proof that language and belonging can cross oceans—and survive.

Stay Ahead on Every Adventure!

Stay updated with the latest news on Escape Artist. Get all the travel news, international destinations, expat living, moving abroad, Lifestyle Tips, and digital nomad opportunities. Your next journey starts here—don’t miss a moment! Subscribe Now!

————————————-

Ethan Rooney is an Irish journalist covering global communities, culture, and niche movements. You can find more of his work here.

About the Author

Ethan Rooney is an Irish journalist covering global communities, culture, and niche movements.

Contact Author

"*" indicates required fields

Stay Ahead on Every Adventure!

Stay updated with the World News on Escape Artist. Get all the travel news, international destinations, expat living, moving abroad, Lifestyle Tips, and digital nomad opportunities. Your next journey starts here—don’t miss a moment! Subscribe Now!