In 2024–25 the Home Office granted citizenship to over 215,706 applicants, 19 percent more than in the year ending March 2024, the highest annual total on record. Among them were 6,131 Americans, a 26 percent surge from 2023, prompted by everything from political uncertainty in the United States to shifts in UK tax policy. Yet behind these headline figures lie thousands of deeply personal stories of migration, memory, reinvention, and resilience from young professionals fresh out of university to families seeking a stable environment in which to raise children.

For applicants like me, Turkish by birth, Portuguese by heritage, British-to-be by residence, becoming British means decoding not only the Life in the UK Test but also the symbolic language of what it means to live in Britain in 2025. Today, becoming British feels less like crossing a finish line and more like crafting a new sense of self, seasoned generously with memories of home. It is to live in a country constantly reframing its identity—through politics, pop culture, weather metaphors, and everyday rituals. From the morning radio on the BBC to debates about the price of a pint, it reflects a shared rhythm of life. There are communal nods exchanged in the rain at a bus stop, and the comfort of walking home with a takeaway on a Friday night, feeling a quiet sense of community, however improvised.

For applicants like me, Turkish by birth, Portuguese by heritage, British-to-be by residence, becoming British means decoding not only the Life in the UK Test but also the symbolic language of what it means to live in Britain in 2025.

Life in the UK Test

For many new citizens, this belonging doesn’t come wrapped in a Union Jack flag. It reveals itself gradually through subtle accent shifts, neighborhood routines, and mastering the silent rules of small talk, queueing, and apologizing when someone else walks into you. It also means enduring the weekly chaos of rail engineering works, sharing in the national pastime of lamenting the state of the National Health Service (NHS), and hearing “this bus is on diversion” just when you thought you had your route figured out. And, inevitably, wrestling with the self-checkout as it barks “unexpected item in the bagging area.”

For me, living in the UK has meant learning to live with uncertainty and a perpetual sense of otherness. During the drawn-out Home Office wait for my visa extensions exacerbated by the COVID-19 lockdown, when leaving the country would have voided my application, I endured months of not knowing if I would be forced to leave the home I had. This ambiguity became its own rite of passage: accepting life in limbo while clinging to the hope of one day fully belonging.

Read more like this Summer in London

Life in the UK with a non-EU passport

Before I obtained my Portuguese citizenship, life in the UK with a non-EU passport often felt like a balancing act with caveats. I am now awaiting a decision on my British naturalization, but looking back, every spontaneous travel plan required a risk assessment: Would I need a visa? Would re-entering the UK be straightforward? Would this trip interfere with my residency timeline?

At airports, I watched EU passport holders’ breeze through the border while I queued with a folder of supporting documents, silently rehearsing my legal right to return to the country I called home.

The same restrictions applied when traveling to Europe. Getting a visa was often an ordeal. One Christmas, the Danish Embassy in London failed to process my visa in time. My holiday plans with my French partner collapsed. We lost our tickets, and instead, I booked a last-minute flight to Turkey just to spend the break with family. I was later told to collect my passport, then return it after the holidays. A month after I resubmitted it—following more embassy security checks and bureaucracy—I received a visa valid for just one month. The process had taken three, cost hundreds of euros, and left me with cancelled travel, lost bookings and mounting frustration.

Read more like this if you are Moving to England

Traveling to Denmark

Another time, traveling to Denmark, my French boyfriend walked through customs unquestioned, while I was stopped and interrogated about my reason for visiting. In Berlin, on a work trip, the questions continued. Despite arriving with colleagues and press credentials, I was the only one asked to show a return ticket, hotel address and proof of my assignment. My mobile data wasn’t working properly at the airport, and the stress of proving I belonged was, once again, mine alone to bear.

Even within the UK, the limitations of my status followed me. While studying for my journalism master’s degree, we were required to complete a six-week internship. I was the only non-EU student in my cohort, and the only one unable to secure a paid, full-time placement because of visa restrictions. My classmates found internships much more easily. I was left juggling legal constraints. On top of that, I had to pay nearly double their tuition fees and prove substantial savings to obtain a student visa.

How long have you lived in the UK

Arriving back into the UK, I was routinely pulled aside by border officers and asked, without much explanation, to justify my life here. What kind of work do you do? How long have you lived in the UK? Do you rent or own? The implication always stung. What does it mean to “prove” your right to be somewhere, when your entire adult life—your work, rent, friendships, taxes, and future—is already embedded in its soil? When you already feel the pull of British life in your bones?

Read more like this: My Harrowing Search for Home

I know that on a political level nationality means everything at the border, but as an individual I acknowledge that national identity is not a single thread, but a layered weave, part pragmatism, part emotion. And let’s be honest—even being British comes with its own layers. You can be English, Welsh, Scottish or Northern Irish. Identity here has always been plural, and belonging often means holding multiple truths at once.

Turkish with my family

I still make menemen during weekends and text in Turkish with my family. But I also carry an umbrella alongside my biometric residence permit, look both ways at roundabouts, and instinctively mutter “sorry” when someone steps on my foot.

In recent months, I’ve spoken with others who, like me, have stitched themselves into British life through official routes, relationships, ritual, and routine. From Iranian filmmakers to American entrepreneurs, Australian writers, and long-time EU residents navigating a post-Brexit Britain, many describe naturalization not as a clean break from their past lives, but as a layering of languages, loyalties, and lived experiences. Some speak of relief, others of quiet pride, but almost all mention a sense of duality. This is the nuance that rarely makes headlines. There are certain themes and trends that the mainstream media always focus on: Trump, healthcare, gun laws, but we need to dwell in the quieter truths. Becoming British does not erase the past; it reshuffles it.

Residents navigating a post-Brexit Britain, many describe naturalization not as a clean break from their past lives, but as a layering of languages, loyalties, and lived experiences.

“My plan was simple: get a master’s degree in Tourism, return to my home country Iran, and start my own tour company,” recalls Mansoureh Farahani, now a travel journalist and filmmaker, who first arrived in the UK in 2011 to retrain for a new career. “But life had other plans. I met my husband, who’s Italian, and that turned a temporary stay into something permanent.” Finding love and a new profession, she adds, “made the UK slowly become home.”

Settling into Married Life

Similarly, Jessica Dante, Founder of Love and London, originally from New York, moved in 2013 after marrying an Englishman. “At 23, I was busy settling into married life, meeting my partner’s friends and family, and trying to get my first full-time job.” Yet it was another political inflection point that finally prompted her to seek citizenship: “When Trump got elected in November 2016, I knew I wouldn’t want to go back to the U.S. for at least another four years. I wanted a more permanent option here.”

For Australians like Georgia Lewis, the visa labyrinth began with a two-year spouse visa in 2011, then indefinite leave to remain and, eventually, permanent residency. “By 2025, I was tired of the endless costs and paperwork, constantly proving at international borders that I had the right to live here,” she explains. “I’m still angry about Brexit, but I figured it was time to end the bureaucracy and become a dual UK-Australian citizen.”

Across these stories, applicants speak of painstaking paperwork. Mansoureh recalls spending evenings reconstructing every trip she’d ever taken, digging through old emails, flight confirmations and passport stamps to list countries visited over a decade. “It felt overwhelming,” she admits. “The fees alone are significant, which adds extra pressure to get everything right the first time.”

Life in the UK Test

Jessica found the bureaucratic obstacles different: “The forms and fees were fine, but the hardest part was finding two British citizens I’d known for over two years to act as referees, and scheduling time for them to sign the form!” She prepared for the Life in the UK Test using the official app and textbooks, laughing that “reading the manual on the bus always sparked a conversation.”

Georgia, speaking from hard-won experience, warns of unexpected pitfalls: “I showed up to the test with the wrong type of ID than I used while booking the test, lost £50, and had to rebook. And I wish I’d kept the pass-slip code, my ex-Home Office friend had to help me via a subject access request to retrieve it.”

New British Habits

But on a day-to-day basis what makes someone feel indistinguishably British? For many it is a small, everyday ritual. Jessica, now vegetarian, savors Sunday roast “for the practice of gathering together in a pub, eating delicious roast potatoes and sharing a pint.” Mansoureh confesses she never used to discuss the weather, “but now I catch myself commenting, ‘Looks like the sun’s trying to come out’,” she laughs, borrowing her husband’s remark that made her feel, at that moment, truly British. Georgia’s litmus test of belonging was more emphatic: “I was appalled by someone cutting the queue.” But then the Aussie side in her decided to loudly call her out. “The orderly queue is sacred, after all!”

What makes someone feel indistinguishably British? For many it is a small, everyday ritual. Jessica, now vegetarian, savors Sunday roast “for the practice of gathering together in a pub, eating delicious roast potatoes and sharing a pint.”

Hospitality is another touchstone. Mansoureh blends her Iranian sense of generosity with Italian warmth and new British habits: “My kitchen is a jumble of simmering stews and bubbling pasta sauces. Inviting people over and making them feel welcome, be that with baklava or a Sunday lunch connects me to my roots and my new life.”

New Citizenship for Living in the UK

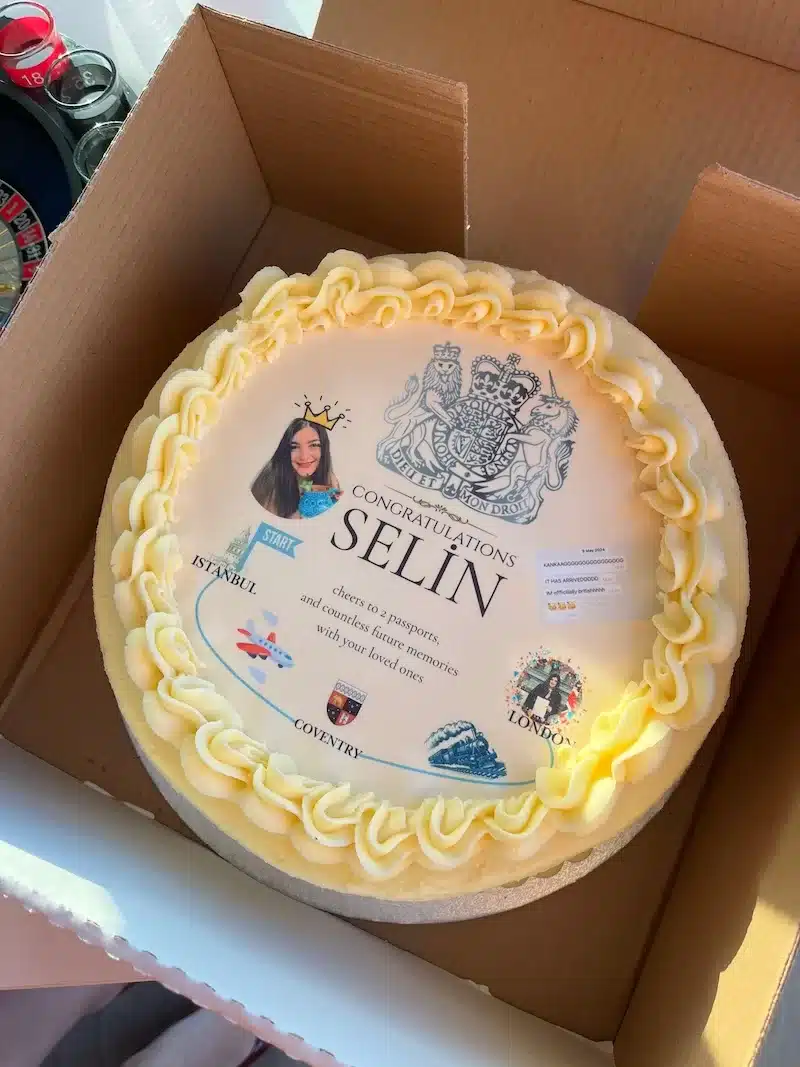

New citizenship is also communal. Among London’s Turkish population, of which I am a part, naturalization has taken on a celebratory and sometimes theatrical dimension. A recent example was the themed passport party thrown by my close friend, Selin Erkut, to mark the occasion of her British citizenship. Guests were invited to dress as quintessentially British icons and cultural references: Where’s Wally, a bottle of HP Sauce, the Queen of Hearts, Jane Austen, and even a packet of fish and chips. Union Jack bunting draped every wall, a photo corner featured a cardboard cut-out of Adele, and the custom-made cake celebrated a life spanning Istanbul, Coventry, and London.

It was humorous, heartfelt, and deeply symbolic—proof that naturalization isn’t always a quiet formality. Sometimes it’s a room full of French fries, royal guards, and Spice Girls outfits, toasting a new passport with Prosecco and pride. These kinds of celebrations reflect a quietly evolving infrastructure of belonging: one that isn’t about assimilation through erasure, but about making space through joy, humor, and community. It’s Britishness not as bureaucracy, but as costume, conversation, and connection.

AI-driven apps: Life in the UK Test

Alongside this, digital tools are radically reshaping the path to citizenship. AI-driven apps now simulate Life in the UK Test scenarios, offer feedback on spoken English, and auto-generate checklists for documentation. Friends in my circle have shared lots of legal representatives or solicitors’ information, comparing legal fees too. There are also study guides and referees (a bizarre quirk of the application process that demands two British citizens sign off on your identity). These aren’t just logistical aids, they are lifelines in a process that often feels labyrinthine and opaque.

But for all the practicalities, fees, forms, and biometrics, what lingers most in these stories is the emotional residue of the journey. As Georgia Lewis, an Australian writer, told me, she had not expected to be moved by the Oath of Allegiance. “But there I was,” she said, “reciting the words next to a room full of people from everywhere—and I suddenly felt it. This is what real Britain looks like.”

For Farahani, an Iranian travel journalist and filmmaker, the turning point came not with a document, but with a feeling: “I may never be 100% British. I am not fully Iranian anymore, either. But I’ve become something in between, and that feels like home.”

Second-Generation immigrants

Meanwhile, for second-generation immigrants, 2025 has brought its own reckoning. As the country faces economic headwinds and contentious debates on migration, the meaning of Britishness is under pressure, yet is also increasingly shaped by diaspora voices. Britishness today can be bilingual. It can wear a hijab, or a sari, or a Pride flag. It can sit between cultures, balancing them like plates at a family meal, sometimes clashing, often complementing.

Britishness today can be bilingual. It can wear a hijab, or a sari, or a Pride flag. It can sit between cultures, balancing them like plates at a family meal, sometimes clashing, often complementing.

Read more like this: Becoming a Citizen of the West

There is also the question of values. What does this passport promise? Security? Representation? Inclusion? For many of us, it is a complicated contract. The UK we have pledged allegiance to is a place of contradiction: where empathy exists alongside hostility, and tradition rubs shoulders with reinvention.

What wisdom would these new citizens pass on? Jessica’s tip: “Keep physical documentation of every address you’ve lived at. My box of old bills and bank statements made my citizenship application a breeze.” Mansoureh adds: “Start saving early and take the Life in the UK Test seriously, study official materials and do mock tests.” Georgia’s counsel is to seek help: “If anything is unclear, ask a friend, a solicitor or use a visa-checking service. A simple mistake can cost you dearly.”

What we all have in common with dual nationals is that we are all layering. We’re balancing old and new histories. Above all, it is to weave your story into the ever-evolving tapestry of this island, reshuffling the past while crafting a sense of belonging that, however improvised, is undeniably yours.

About the Author

Istanbul-born Mergim Ozdamar is a London-based marketing consultant and freelance writer with a passion for food, culture, and travel. She is the editor of The Mediterranean Magazine.

Contact Author

"*" indicates required fields

Stay Ahead on Every Adventure!

Stay updated with the World News on Escape Artist. Get all the travel news, international destinations, expat living, moving abroad, Lifestyle Tips, and digital nomad opportunities. Your next journey starts here—don’t miss a moment! Subscribe Now!