Editor’s note: This is part two of a two-part feature. Click here to read Part 1.

Part 2: Bringing It All Back Home

The Scent of Love

In 1492, after their reconquest of the Iberian Peninsula, the rulers of Spain issued the Alhambra Decree, ordering the expulsion of all practicing Jews. The edict was mainly driven by concern that practicing Jews would have a malign influence on many converso New Christians – former Jews who’d converted to Christianity in the wake of a massive pogrom a century prior.

The Sephardic Jews forced out of Spain and Portugal fled east, with some ending up in Scandinavia and others settling across the Ottoman Empire. The Nefussi family ended up in Livorno, Italy, on the Tuscan coast. Fast-forward to the early 20th century, when they had a daughter named Anna, who would later move to Istanbul.

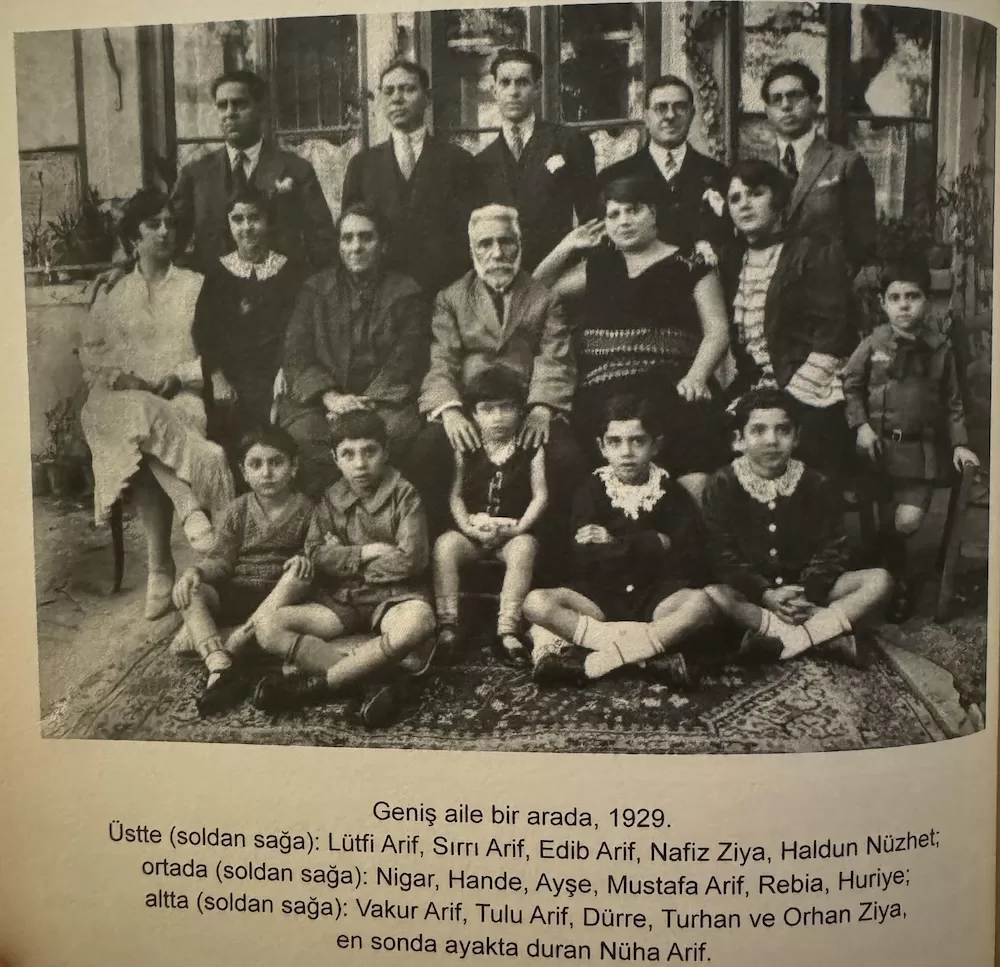

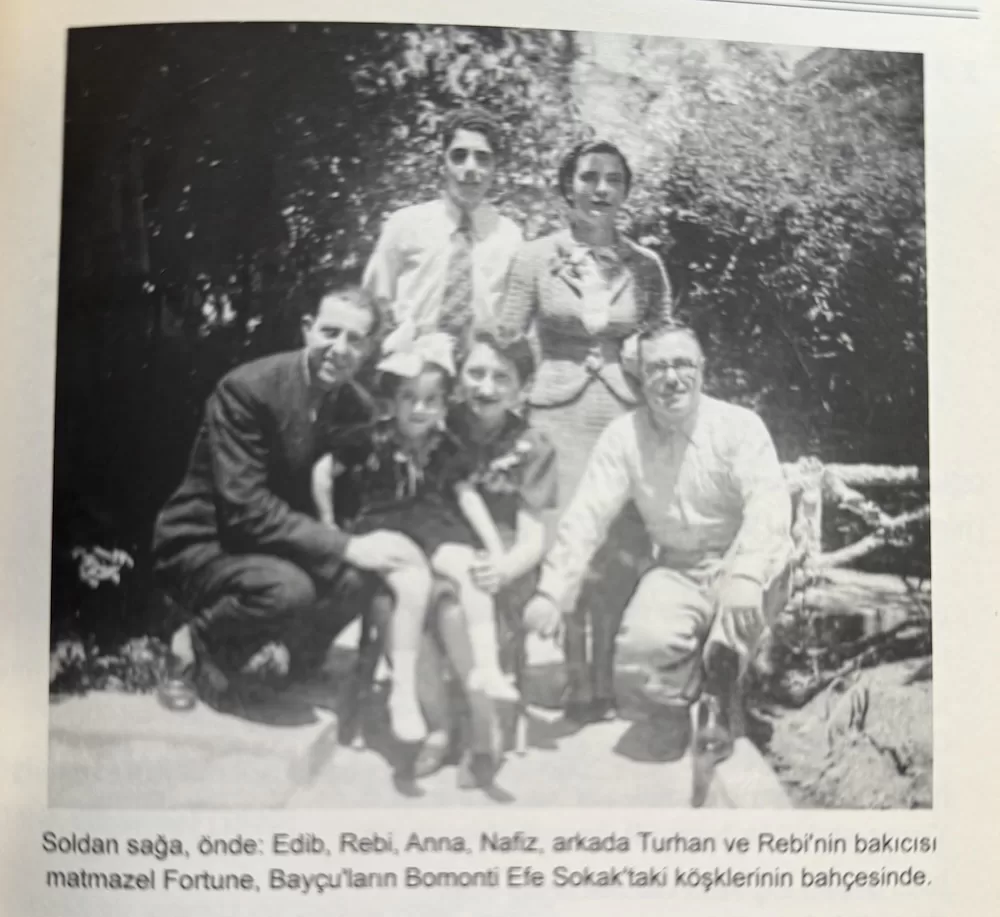

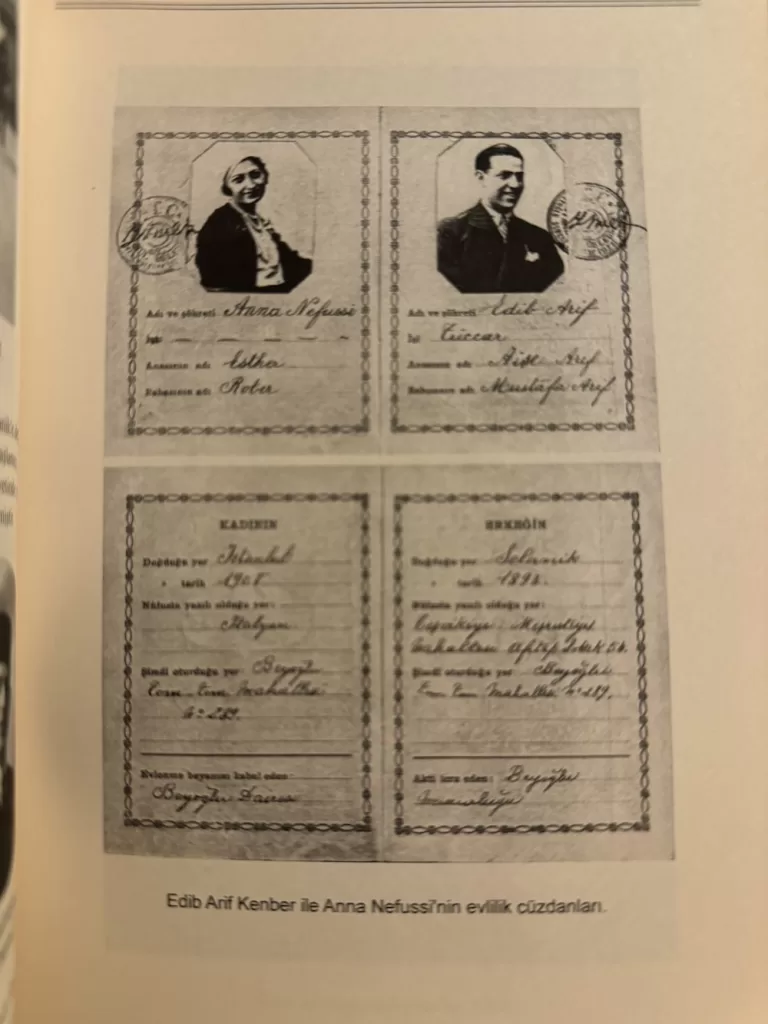

In the meantime, the family of Mustafa Arif Efendi settled in Thessaloniki for generations. He married and had 10 children, though two passed away young. Of the eight that reached adulthood, all five sons were educated in Europe and carved out impressive careers. Enver, as detailed above, became a chemist and soap maker, and my great grandfather Edip, after university in France, a perfumer.

“Je tombe des nues” (‘I’m falling from the clouds.”), Anna exclaimed. “Mais dans mes bras mademoiselle” (“But into my arms, miss.”), my grandfather replied.

During the Turkey-Greece population exchange of 1923, in which nearly two million people crossed the border to their new homeland, Mustafa Arif Efendi and his family moved from Thessaloniki to Istanbul. He was fluent in French, a language that was the mark of aristocracy in Turkey at that time, particularly in Istanbul, where cultures, faiths, and languages mingled on bustling streets.

That and his charming perfume store on Istiklal Caddesi, the city’s main pedestrian thoroughfare, underscored “his refined taste and entrepreneurial spirit,” Bilgi writes in the book. He could not have found a better location than the hub of Istanbul commerce and society, attracting intellectuals, artists, diplomats, and the city’s elite.

Edip’s perfumery became a local touchstone of sophistication. One day, a lovely young woman with an Italian passport strolled in. Edip recognized her from his previous store and let her know he remembered her. The woman said she found the new shop simply stunning.

She felt nearly overwhelmed by the scents and the setting. “Je tombe des nues” (‘I’m falling from the clouds.”), Anna exclaimed. “Mais dans mes bras mademoiselle” (“But into my arms, miss.”), my grandfather replied. So began their enchanting love story, which would lead to marriage and last the rest of their lives.

Turning Toward the EU

Months after Bilgi’s eye-opening family reunion at the hotel, my father sat me down to tell me that he had decided to apply for Portuguese citizenship. To explain what he meant, I’ll have to rewind a little.

In 2015, Spain and Portugal announced a major new policy that many view as a historical apology: they would begin offering citizenship to anybody who could prove they descended from Sephardic Jews forced out of the Iberian Peninsula during the Expulsion spurred by the Alhambra Decree. Although Spain ended its citizenship program in 2019, these laws have enabled countless families to reconnect with and renew a long-lost heritage, including mine.

My family’s decision to apply was driven not by a desire to relocate, but by an opportunity to reconnect with our ancestral roots and gain EU citizenship, which meant greater opportunity and freedom of movement. Like many other Turkish nationals or Sephardic descendants, obtaining an alternative passport could serve as a plan B for us, especially given Turkey’s economic and social peril in recent years.

Realizing that we could apply to become EU citizens was not a part of my thought process when I learned of my family’s Dönme background. As my father explained their decision – Spain required proof of Sephardic ancestry, a familial connection to Spain, and passing language and culture tests, while Portugal’s law focused on lineage – I could hardly contain my excitement. Since I’d been a little girl I had wanted to explore different cultures.

Moving to the UK in my 20s, I had become the family’s de facto diplomat and ambassador.

Now here was the opening of a new door, a new world of endless opportunity. If you hold a Second-World passport, you’re applying for visas and submitting extensive documentation nearly every time you want to cross a border.

Plus, Turkey is a mainly Muslim country so I’m always being asked if I’m a terrorist. Putting all that behind me would be incredibly empowering and a massive relief. In mid-2019, we started the application process with the help of an advisor in Istanbul and his business partner, a Portuguese lawyer in Lisbon.

Here I was, a Turkish national in the USA with UK residency rights empowering someone in Turkey to collect documents about my secret Jewish background so I could apply for Portuguese citizenship.

Each family submits one joint application, so my grandma and father had to officially prove their Jewish ancestry. To do that, they needed official approval from Turkey’s Chief Rabbi. The advisor prepared a strong case for us, explaining our family tree, Mustafa Arif’s diary details, and more. Bilgi’s extensive Jewish connections in Istanbul were extremely helpful.

In late 2019, I traveled to the USA for a few months at a crucial moment in our application process. One day I had to visit the Turkish Consulate in Miami to give power of attorney to a man back in Istanbul helping our advisor gather documents. Here I was, a Turkish national in the USA with UK residency rights empowering someone in Turkey to collect documents about my secret Jewish background so I could apply for Portuguese citizenship.

Could I be any more of a global citizen? I thought to myself. Yet somehow, it all felt natural. But back then I couldn’t explain what was happening to anyone because I didn’t think they would understand.

The Long Road to Citizenship

When we finally submitted our application in the last weeks of 2019, we thought we’d made it through the hard part. But our work had just begun. First, a global pandemic would shut down most government work for many months, but even after that it would be four more years of waiting and hassles and waiting some more.

Initially, any request for an update from Portuguese authorities was met with aggression. Finally, I was given an access code to an online portal where I could track the status of our application as it moved through 7 steps. I visited the site so often it soon became a browser favorite. But nearly every visit resulted in disappointment, seeing again the lack of progress. At one point, my dad’s and sister’s applications moved forward while mine did not. Worried, I made a few calls and found they had lost my birth certificate and criminal record. I sent them again.

We heard similar stories from friends and relatives who had applied, but most of their families had been openly Jewish during the intervening centuries, not Dönme. Maybe all applicants had a similarly difficult experience, but the bar we had to clear was much higher. Most applicants were openly Jewish and merely had to prove their links to the Iberian Peninsula. My family had to prove that as well as our Jewish ancestry, which was of course not apparent given our Muslim names.

By June 2024, nearly five years had passed since our initial application and my Schengen visa was about to expire. As I navigated the bureaucratic maze to secure my Portuguese citizenship, I couldn’t help but think of my ancestor Dönmes who endlessly navigated their own complex identities. Their tightrope walk between two worlds—Jewish and Muslim, private and public—mirrored my struggle to reclaim the heritage they’d taken great pains to retain.

Each bureaucratic hurdle felt like a test of my resolve, another reminder of my non-EU status, which only intensified my desire for a more secure and stable future. Then, one day this past July, our Istanbul advisor sent me an online form to apply for my Portuguese birth certificate. I filled it out and three days later received an email telling me I was a Portuguese citizen.

I could barely believe my eyes. I was in a hotel room in Çeşme, on the Aegean Sea in western Turkey, when I received the news, and I felt as if the ground had shifted beneath my feet. My life had changed in an instant. It might be hard to believe, but I started to feel the sense of security and belonging I’d always been missing. The possibilities that lay ahead—in terms of work, travel, and simple human freedom —felt limitless. But I knew what I had to do first.

Returning Home for the First Time

Now that I was a Portuguese citizen, Lisbon became much more than a beautiful city I’d once visited. I started to see it as almost part of my own identity. My sister and I decided to celebrate our new nationality, and get our Portuguese ID cards, with a visit to its capital.

Arriving in late August, we stayed in Alfama, one of the city’s oldest districts, which still retains its medieval character, with narrow, twisting alleyways and apartment blocks squeezed together. From the Arabic word “Al-hamma,” which like the Turkish “hammam” means “baths,” the name is a reminder of Moorish rule, which started in the early 8th century and ended with the Reconquista that ultimately drove out the families of my ancestors.

Lisbon felt like a distant cousin of Istanbul, echoing its spirit, its pulse, and, in a sense, my own journey.

Beyond its modern-day allure, Lisbon, much like Istanbul, is a city where the past and present are intertwined — history, culture, and stories of migration are ever-present. At the Conservatória dos Registos, the government office for public records, we met Joaquim, an Indian-Portuguese man (originally from the Indian state of Goa, a former Portuguese colony) whose main job is to help Sephardic Jews and Israelis obtain Portuguese citizenship.

He took us to the counter where we would apply for IDs, where I signed the documents and posed for the ID photo. The elderly lady at the counter insisted on speaking in Portuguese, despite knowing I didn’t speak the language. “So you’re Portuguese,” she said sharply at one point, “but don’t speak Portuguese?” I understood her, and thought about giving her a piece of my mind. Thankfully, Joaquim intervened and resolved the issue.

After we returned to pick up our ID cards, I began to see the city with fresh eyes. No longer just a visiting Turkish woman; I was someone who belonged, someone with roots here, a descendant of Iberian exiles. Walking Alfama, where many Sephardic Jews had lived before the Expulsion, I felt a deep connection. The streets whispered stories of resilience and survival, some of which were now part of my own narrative. We passed the Shaaré Tikvah Synagogue, in Santo António,

a powerful reminder that the city is still home to a Jewish community today.

I was reminded that my roots, scattered across the lands of the Ottoman Empire and Iberia, are part of this complex tapestry. Every building seemed a living testament to an endurance that, despite centuries of upheaval, continues to shape its people today. Like many great cities, Lisbon is evolving by revisiting and reinterpreting its past. In recent years, it has emerged as a hub for digital nomads, exiles, and various Western expats, who have settled in to launch countless new businesses, chic restaurants, and stylish cafes and cocktail bars.

Istanbul and Lisbon are both known for their seven hills, their cobblestone streets winding through centuries-old neighborhoods, their stunning, sweeping views over vast bodies of water. These similarities resonated deeply with me. Walking through my potential future home, Lisbon felt like a distant cousin of Istanbul, echoing its spirit, its pulse, and, in a sense, my own journey.

Thinking back to the past, I wonder where exactly my Sephardic Jewish ancestors lived. Could it have been here, in the winding alleys of Lisbon? Or perhaps in the bustling Andalucian capital, Seville, before they were forced to flee? I cannot trace my family tree back to the 15th century to know for sure, but I like to imagine their journey took them through these very streets. With Portugal offering me the opportunity to reconnect with this heritage, I feel a renewed sense of belonging and welcome.

I cannot trace my family tree back to the 15th century to know for sure, but I like to imagine their journey took them through these very streets.

My journey has been one of discovery, not just of places but of self. I now know, deep in my heart, that we need not belong to just one place. Especially in this era of identity politics – when a Turkish woman in the EU is likely to be seen as a Muslim immigrant and a tourist, or potential terrorist, rather than a citizen with a local history – it’s crucial that we learn to accept and embrace our multifaceted identities. In a world that seeks to define us in narrow terms, it’s these intersections and complexities that make us who we are.

Visiting Lisbon, what struck me most was how familiar the Portuguese people suddenly seemed to me, almost like the warmth I’ve always known in Turkey. There is now an unspoken bond, a shared sense of community and kindness, that transcends borders and histories.

Despite the centuries and the kilometers between us, we are not so different after all. People, I’ve found, are all too often judged on their passport, rather than their humanity.

————————

Epilogue: I’m now living in London, where I’ve registered with the Portuguese Embassy. Portugal is a wonderful country with a lively culture, and Lisbon is beyond special to me, as the place that made my identity whole. Might I make Portugal my home, at some point? I can’t say for sure. But I can say that the freedom of movement and absence of intrusive inquiries I now enjoy is an invaluable gift, given to me by Portugal. For that, I will be eternally grateful.

————————

Istanbul-born Mergim Ozdamar is a London-based marketing consultant and freelance writer with a passion for food, culture, and travel. She is the editor of The Mediterranean Magazine. Follow her on X.