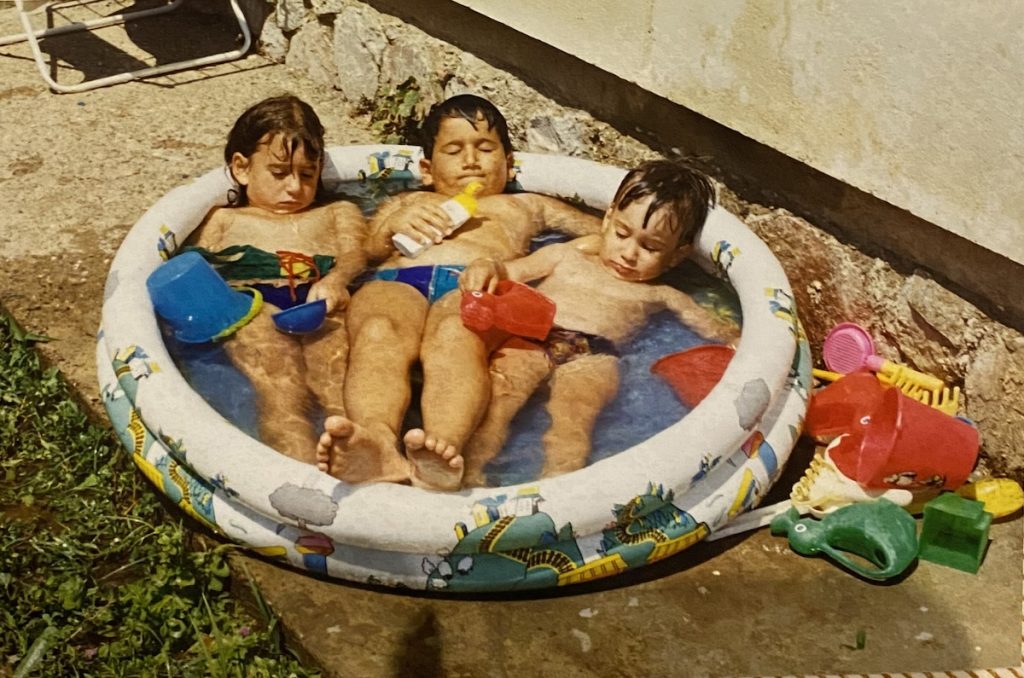

When I was around seven years old, my parents took me to the thermal pools of Pamukkale, a four-hour drive inland from our coastal hometown of Izmir. I remember being vaguely excited about the trip, but unsure what to expect. I loved the sea, but this place, as they’d described it to me, sounded completely different from the enchanting azure of the Aegean.

The scene seemed magical and otherworldly, the pools shimmering under the sun like gems, embedded in white limestone terraces cascading down the cliffs.

When we arrived, I could hardly believe my eyes. I was struck by the color of the water. Pamukkale’s pools are a hazy, milky turquoise, oceans away from the deep sea blue back home.

Moving closer, I saw the steam rising into the cool morning air. Ancient Romans bathed in these same pools thousands of years ago, my parents told me. My eyes were wide. The largest of them, they added, is known as Cleopatra’s Pool, named after the famed queen who enjoyed its waters back when this city was called Hierapolis.

Its waters are said to be nutrient-rich, and its bottom is strewn with marble columns that crumbled in an earthquake many centuries ago. I waded in, feeling the smooth stone beneath my feet. The warm water soothed me, and I dove in headfirst. I remember floating on my back and gazing up at the sky, feeling supported as I mentally drifted back in time.

I swam among the ruins of a Roman temple, the scattered, broken columns once dedicated to Apollo softened by centuries fully immersed. I imagined the people who walked among these columns. I could feel their presence, as if the pool were alive, a liquid time capsule connecting me to gods, emperors, and ancient rituals.

Looking back, I experienced a brief communion with history, an odyssey into the past. Surrounded by the remnants of a lost civilization, I connected to the ancient world in a way that felt intensely personal.

This stirring moment spurred my lifelong fascination with water, a good soak, and the power of age-old rituals.

At 10 I learned to windsurf, and within a few years I was teaching it as a coach in the turquoise waters off Çeşme. Being on the water became everything to me—the push of the wind in my sail, the rhythm of the waves. In winter, I trained with the regional swimming team so I could stay in water year-round.

I was probably 18 when I had my first kese köpük (scrub and soap), at Istanbul’s Çemberlitaş Hamamı. Tucked between drab shops a stone’s throw from the famed Grand Bazaar, the 450-year-old hamam, with its grand domed ceiling, was built by the best of all Ottoman-era architects, Mimar Sinan.

Despite its popularity and history, it felt like a personal sanctuary. Being scrubbed and enveloped in soap bubbles felt transporting, cleansing body, mind, and spirit. Whether in the Aegean, the hamam, or the pool, each immersion connected me to nature, to the builders, gods, and mariners of centuries past. It was somehow both ancient and eternal.

Years later, as a struggling artist in New York, I sought the same connection in the East Village. The winters were brutal, the wind biting through layers of clothing and leaving me chilled to the bone. Some great advice from locals led me to the Russian and Turkish Baths, affectionately known as “the banya,” and I instantly latched on to its rituals of soaking and socializing.

The harmony of hot and cold, steam and water, seemed to optimize the mind-body connection. It was in the banya, covered in sweat, that I met some of the most interesting people of my life—writers, healers, fellow artists, and “regulars” who’d been going there for 50 years. Once again, I had found my place in the water.

Soon after moving to San Francisco, I found a way to make bathing an even bigger part of my life. Back in New York I’d come across the platza, in which a practitioner uses a bundle of twigs to increase the participant’s circulation and push heat and steam into the skin and body. But at Archimedes Banya in San Francisco Bay, the staff performed the platza with such skill and passion and effectiveness I immediately decided I needed to learn it myself.

After watching a powerful session, I approached a Russian man who seemed well versed in the tradition and asked if he could introduce me to the manager. I expressed my deep interest in learning and performing platza, and to my surprise and delight, the manager hired me on the spot. From then on, I immersed myself fully in the ritual.

I learned that the bundle of branches is called a venik, and that the twigs are often taken from oak or birch trees, which have a stronger smell. I also learned that the preparation of the venik is an art in itself. Each twig is inspected for sharp points, knots, and acorns, which could cause discomfort.

The branches are then soaked in water for hours, which keeps them from becoming floppy in the heat. I learned to save this soaking water to later pour over the hot sauna rocks, creating fantastically aromatic steam that transports the sauna to the heart of a forest.

A well-done platza involves a sequence of techniques. It starts with fanning, a circular motion of the venik to guide steam so it envelops the body, helping beads of sweat form.

Next is sweeping, when the venik makes light contact with the skin to brush away the sweat and toxins that have emerged from the pores.

During compression, the venik is heated by raising it above the head, allowing steam to collect in its leaves before it is pressed on to the body. The heat can be intense, yet this is intentional, as it serves to stimulate blood flow and release tension. Finally, tapping, almost a rhythmic drumming, relaxes the muscles and helps release any remaining tension.

Done right, platza can be profound. The hot steam enveloping the body, the sensation of leaves against the skin, the rhythmic motions of the practitioner—all of this can create a deep, almost meditative state of relaxation and presence. The ritual is best finished off with a dip in an icy-cold plunge pool, a shock to the system that brings a rush of adrenaline and euphoria.

Much like my swim in Cleopatra’s Pool, my exposure to platza at Archimedes served as a bridge to another world, a connection to age-old traditions. It also seems fitting that Archimedes was an ancient Greek philosopher, just as Hierapolis, now Pamukkale, was an ancient Greek city. Direct links to millennia long past, and to my personal history.

At Archimedes, I discovered a new dimension of my lifelong love affair with water—one of healing, and community—and it sparked my creative fire. I committed to developing and launching a platform that could highlight and connect people who bathe and their experiences—a sort of “Humans of New York” for the bathhouse.

My research led me to WET, an avant-garde publication from the late 1970s that treated bathing as an art form, a cultural practice worthy of exploration and celebration. A bold new magazine, I decided, would be the perfect medium to spread bathing art and culture. Most bathing spots ban electronics, which makes them a great place to read and talk.

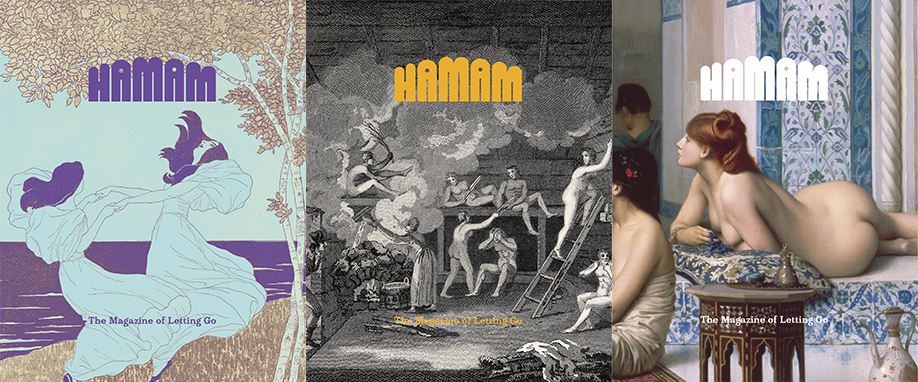

The concept came to me one day in a flash of inspiration. Since I’m Turkish, I knew the name had to be Hamam. But imagining it was one thing; making the magazine a reality proved to be one of the most challenging, and rewarding, experiences of my life.

Today I’m beyond proud about Hamam, a quarterly print publication celebrating the art and culture of bathing. Featuring essays, photos, interviews, poems, short stories, and more from around the world, Hamam is more than just a magazine—it’s a philosophy of letting go and having a good soak.

It’s also a reflection of my journey, from connection and exploration to cleansing, healing, and beyond. Ivy League history professor Ethan Pollock, author of Without the Banya We Would Perish, describes the hamam experience like this: “You open up your pores and sweat out all the evilness, all the nastiness.”

I’d say there’s a lot more to it than that. But that’s surely a good place to start.

——————

Based in Taos and Izmir, Ekin Balcıoğlu is a visual artist and editor and co-founder of Hamam: The Magazine of Letting Go. Find her at https://hamam.co/ & on Instagram.

Ekin Balcıoğlu