This is an experiment. The insanity engulfing Washington now is so overwhelming that I had to get far away from it. I wanted a place that very few people knew anything about. Then a challenge occurred to me.

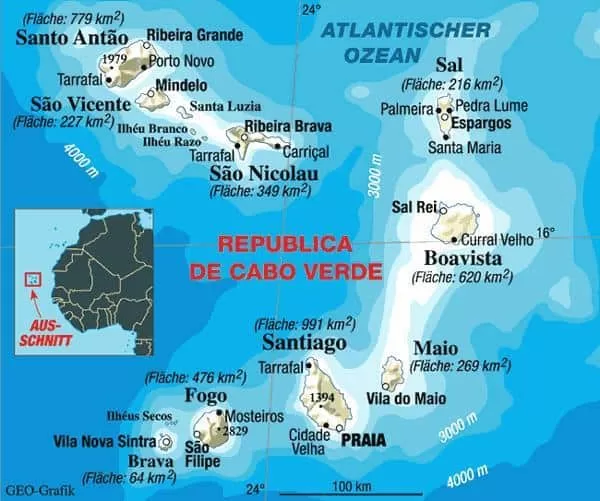

What could I learn about such a lost unknown place that Escape Artists would find interesting? Could I possibly write something that would intrigue them? So here we go – let me know how this experiment works. The place I picked is an island country in the Atlantic Ocean 400 miles off of Africa called… Cape Verde.

Sorry about the German above, but it’s the best map around. That’s because hordes of Germans escape from their winter to lie on the beaches of Sal (non-stop flights from Frankfurt) and turn their skins bright pink. That’s all they do. They don’t go anywhere else or explore any other islands. Their only movement all day is to turn over back-to-belly so both sides get equally lobster-roasted.

But it wasn’t the Germans who created Cape Verde, it was the Portuguese. The Romans called the islands “Gorgades” – the land of the Gorgon monsters, the most famous being Medusa, killed by the Greek mythological hero Perseus – but never settled there. No one else did either, so when ships sent by Portugal’s Prince Henry the Navigator (1394-1460) to explore the west coast of Africa reached them in 1456, they were uninhabited.

A dozen years earlier, Portuguese explorers rounded the westernmost point on the African continent, which they called Cape Green, or Cabo Verde, as it was densely covered in vegetation. (Now called Cap Vert as it’s in Senegal, which is a Francophone country.)

For some mysterious reason – maybe to attract settlers – Prince Henry decided to call these arid volcanic islands Cabo Verde as well.

The settlers came, the first in 1462 on an island they called São Tiago (Santiago). Why they stayed once they quickly learned the place was the opposite of green – mostly a burned-out desert wasteland with some acacia thorn trees – is a good question. The answer turned out to be slaves.

The Portuguese were the first Europeans to explore Africa’s west coast, and they soon learned that tribal chiefs were eager to sell captured members of other tribes into slavery. There was a market, although not large, for slaves in Europe – and the settlement on Santiago turned out to be a useful transshipment point from the places in Africa where slaves were sold to places in Europe where they were bought.

Then Portugal began its colonization of Brazil in 1500, sugar from sugar cane plantations became enormously profitable to export to Europe, the plantations required massive numbers of slave labor, and by the mid-1500s, the transatlantic slave trade had made Santiago rich.

More settlers came to found more settlements, slaves escaped into the mountains and farmed wherever there was a bit of water, Portuguese men and the prettiest African women connected, and the initial generations of café au lait Cape Verdean creoles came to be.

Pirates and privateers came as well, to loot and pillage. Sir Francis Drake, encouraged by Queen Elizabeth, sacked Santiago’s main town of Cidade Velha in 1585. Aside from these occasional annoyances, Santiago flourished from the slave trade for the next two hundred years. Then the Brits put an end to the slave trade, and by the early 1800s, Cape Verde’s economy had collapsed.

And who should come to the islands’ rescue but the Brits, who discovered that São Vicente had a fabulous harbor at Mindelo Bay perfect for a coaling station to supply the new steamships plying the Atlantic.

Prior to 1838, the island was uninhabited and used only for cattle pasturage. As one of the world’s foremost trade posts for coal, Mindelo quickly became a flourishing cosmopolitan town filled with millionaires. Even more so after 1885, when it became the switching station for the first trans-Atlantic telegraph cable.

Cape Verdeans, especially those who lived on the live volcanic island of Fogo, learned they had another resource – themselves. They had a particular knack for the hard labor of whaling, and were sought after to crew on 19th-century American whaling ships.

Thus, started the Cape Verdean diaspora to America, particularly New England. Large communities of Cape Verdeans are found today in such places as Nantucket and Providence.

(There are now some 600,000 Cape Verdeans living abroad now, about half in the U.S. – more than the 500,000 who live in Cape Verde itself.)

The Cape Verde economy collapsed yet again when steamships switched from coal to diesel fuel after World War II. And to its rescue rode not the Brits but… the airplane.

European airlines such as Alitalia built an airport on the deserted desert island of Sal for a refueling stop between Europe and South America. Then South African Airlines began flying from the US direct to South Africa – with a necessary fuel stop in Sal.

This was a long flight. My only memory of here prior to now was groggily getting off the plane from JFK on the way to Joburg years ago, looking out to some volcanic peaks in the distance without a shred of green, and getting back on the plane thinking there sure is nothing here. How wrong I was.

There are perfect beaches of perfect sand and perfect pure turquoise water with soft gentle waves on Sal, with perfect weather 350 days of the year. The airport at Sal has brought a tourist boom. You can fly here non-stop from Boston for $650 round-trip.

There are non-stop flights from Europe and the U.S. to Praia (the capital on Santiago) now – but that’s brought a business, not a tourist, boom. You only see the occasional tourist on any island except Sal. Remember all those Germans.

The businessmen are here because Cape Verde has reinvented itself once again. It has become one of the best places to do business in Africa.

Now why is that? Here the story starts to get interesting. Not historically, but relevant to today.

You can see one thread – Cape Verde geographically positioned to prosper from the slave trade, then the coal trade, then the jetfuel trade, then the tourist and business trade. But that’s just geography, and there are factors far more important.

Those factors are human. They are cultural. What makes the difference between failure and success for a race, a society, a nation, is not genetic. The average IQ of Cape Verdeans is 76, which is frighteningly more than one full standard deviation below the norm of 100. The critical difference is not racial, it is not IQ, it is cultural values.

Cape Verde has no natural resources. It is so dry and waterless there’s not one single river flowing year-round on any of its islands. Getting crops to grow out of its parched, rocky soil is really hard work. The ocean has a lot of fish, but places to locate along its rocky shores are few. Making a living here is not easy.

Yet, Cape Verde has survived and even thrived – because of its human resources, a mix of attributes comprising the Cape Verdean character.

Cape Verdeans are affable and easy-going; they love music and dancing and drinking their moonshine rum called “grogue“; they are peaceful with very little crime or violence; they are dependable and reliably responsible as workers; they are devout Christians (mostly Catholic); and they are honest. Their honesty is what most critically sets them apart from the rest of Africa.

Since 1971, the UN has maintained a list of Least Developed Countries, the worst of the world’s worst off. 33 out of the list’s 49 are in Africa (15 in Asia and 1 in the Americas: Haiti). In the almost 40 years since the LDC list’s inception, only two countries have succeeded in graduating off it: Botswana and Cape Verde.

Botswana did it with money from diamonds and South African white-run safari tourism. Cape Verde did it by overcoming a KGB-sponsored Communist dictatorship.

In the 1950s, the Soviets began targeting Portugal’s African colonies – Cape Verde, Portuguese Guinea, São Tomé, Angola, and Mozambique – for subversion. KGB agents in the Communist Party of Portugal focused on students from these colonies studying in Lisbon. For Portuguese Guinea and Cape Verde, they settled on a student of agronomy, Amilcar Cabral.

Bankrolled by the KGB, Cabral set up a Marxist guerrilla group called the PAIGC, a Portuguese acronym for African Party for Independence of Guinea and Cape Verde, in 1956. Throughout the 60s, Cabral’s guerrilla recruits, trained and heavily armed by Cuba and the Soviets, waged a war against the Portuguese military in Guinea – but failed to arouse any enthusiasm among Cape Verdeans.

The KGB propaganda machine made Cabral an international celebrity, an African Ché Guevara. He gave speeches in the Soviet Union praising Lenin as “the greatest champion of the national liberation of the peoples.” Assassinated in 1973 by a PAIGC rival, he remains a Leftist hero to this day.

The PAIGC was on the verge of defeat when the KGB engineered the overthrow of the government of Portugal by the officers of the Communist MFA, Armed Forces Movement, in April 1974. The new Communist government in Lisbon ordered the surrender of Portuguese Guinea and Cape Verde to the PAIGC.

Without a single vote cast by Guineans and Cape Verdeans, the PAIGC one-party dictatorship – led by Amilcar’s brother, Luis Cabral – was established in September 1974, and recognized as the legitimate government by the UN. Cape Verde was now a colony of re-named Guinea Bissau, which was itself a Communist colony of the Soviet Union.

When Luis Cabral was overthrown in 1980 (the KGB decided to replace him with another guy), the Cape Verdeans saw their chance, declared their union with Bissau dissolved, and gained full independence. Yet, still, it was one-party rule by the Cape Verde branch of the PAIGC, the PAICV (African Independence Party of Cape Verde). But not for long.

All through the 80s, more and more of the economy was privatized, and more political opposition was allowed. Finally in 1990, full multi-party democracy was launched. The next year, the PAICV lost parliamentary and presidential elections, and there was a peaceful transfer of power to the MPD (Movement for Democracy) party.

The MPD promoted free trade, free market capitalism, and free elections. Its policies moved the PAICV away from socialism and towards the right. Today political rule is almost evenly divided between the two. Cape Verde is a true democracy.

Transparency International’s Corruption Index now ranks Cape Verde #48 out of 180 – only Botswana has less corruption (#34) of any African country (Guinea-Bissau is #171, tied with North Korea – note that the U.S. is only #16).

The rankings don’t give much of a full picture, however. Corruption in Africa is simply overwhelming – thus, its relative lack in Cape Verde is like night and day by comparison. That’s why so many companies doing business in Africa have their offices and plants in Cape Verde now.

They get whatever products they want from some African country shipped to them in Praia or Mindelo, process and package it (like fruit into juice), then transship it to Europe, Brazil, the U.S., etc. All without endless bribes to officials, courts, and police. Cape Verde is a businessman’s paradise compared to the rest of Africa.

And the resultant prosperity is showing, bursting out all over. The government is spending money on new schools, hospitals, and roads. Impressive new homes and condos are sprouting up everywhere. People are nicely and cleanly dressed. There’s still lots of poverty but no hunger.

Character counts. Freedom and honesty work. High moral values are more important than high IQ. These are lessons taught by the example of Cape Verde. The world would be far freer and more prosperous if more countries would learn them – the United States included.

OK – so much for learning, now let’s have some fun. The best way to start is with a local beer. They make good beer in Cape Verde, and the best should be the favorite of Ayn Rand fans and Objectivists:

Watch out though – it’s 8%…

We’ll skip the tourist beaches on Sal and go to the locals’ favorite, Tarrafal on Santiago:

Then we’ll head for the coolest island of all of them, San Antão. To get there, we fly from Praia to Mindelo, then take a ferry to Porto Novo, where our driver meets us to drive over the mountain to Ribeira Grande. This is a drive you’ll remember for the rest of your life.

Yes, it’s steep and super-curvy with drop-offs of thousands of feet – but our driver is safe and slow so it’s not scary, just astoundingly spectacular. At the top, there’s a volcanic crater, and from the rim you look down into the gorgeous valley of Paúl (pow-ool).

The drive down is even more spectacular – and impressive, as villagers have built thousands of stone terraces, even on high ridges and mountain tops:

We reach the coast and go past Ribeira Grande to this tiny, totally laid-back funky fishing village, Ponta do Sol, to watch the fishermen bring in the day’s catch, gorge ourselves on fresh fish and lobster for a few bucks (washed down with a couple more Ego beers), then go for a swim in the natural ocean pools:

Then it’s back to Ribeira Grande to locate a local moonshiner. Homemade booze is legal in Cape Verde, and the folks are real artisans at making it. Sugar cane is crushed and the juice extracted, then fermented for two days. Then it’s distilled. Here’s a typical “distillery” operation out in the bush:

The product comes out of a pipe into a bucket, ready to drink or be bottled:

This is George, ready to serve you a sample of his product in a piece of coconut shell.

Cape Verdeans are very proud of what they consider their national drink, which they call grogue (“grog”). We’d call it rum, and while it’s homemade, it’s smoother than any commercial rum or other kind of booze you’ve ever had. It goes down your throat like water.

So you’ve got to be careful – for it’s 140 proof. Pretty easy to get wasted. Thank heavens our driver doesn’t touch a drop.

With our supply of grogue, we decide we’ll just park it here in San Antão for a few days and let the craziness of Washington drain out of us. All of the world’s insanity seems so far away here. So peaceful, so friendly, and so beautiful:

Yep, we think we’ll just stay. We’ve found the perfect escape hatch for Escape Artists.

Carpe diem. Life is short. The time for a great adventure is now.

Here are a few additional articles you may enjoy reading:

You Must Prepare Your Exit from South Africa Immediately

About the Author

Jack Wheeler is Escape Artist’s World Adventure Expert and has also been called the “real-life Indiana Jones” by the Wall Street Journal. He has had adventures in every country in the world: all 193 UN Member States, additionally 115 distinct territories and dependencies. He’s had two parallel careers: one in adventure and exploration with Wheeler Expeditions; the other in the field of geopolitics. He also received his Ph.D. in Philosophy from the University of Southern California, where he lectured on Aristotelian ethics.

Contact Author

"*" indicates required fields

Stay Ahead on Every Adventure!

Stay updated with the World News on Escape Artist. Get all the travel news, international destinations, expat living, moving abroad, Lifestyle Tips, and digital nomad opportunities. Your next journey starts here—don’t miss a moment! Subscribe Now!