Afghanistan – The Doormat of Empires

I first traveled through Afghanistan in 1963 at age 19. You could go anywhere. I met guys who bicycled from Herat to Mazar-i-Sharif to Kabul with no problem. I saw women in full tshadris (the complete burqa with a mesh netting to see through) walking next to women in high heels, knee-length skirts, and beehive hairdos on the streets of Kabul. It was a wonderful, exciting – and peaceful – place.

I was back in 1973 and the end had begun. It’s been a ghastly mess ever since. The U.S. military has been bogged down there for the last 17 years with no light at the end of the tunnel. Thus, we frequently see, from news magazines like TIME to journals like The Diplomat, the old bromide of Afghanistan being “The Graveyard of Empires.”

It’s a myth. Afghanistan has been steamrolled by conquerors for millennia.

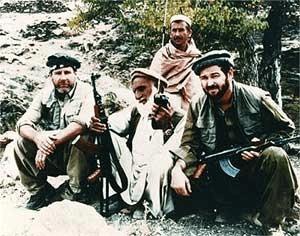

I spent considerable time in Afghanistan all through the 1980s with various groups of Mujahaddin fighting the Red Army of the Soviet Union. Take a look at this picture:

When my son, Brandon, was a senior at the Virginia Military Institute in 2005, one of his courses was on Modern Military History. In his lecture on the 1980s Soviet war in Afghanistan, the professor showed this photo slide of “four typical Mujahaddin fighting the Soviets.”

When my son, Brandon, was a senior at the Virginia Military Institute in 2005, one of his courses was on Modern Military History. In his lecture on the 1980s Soviet war in Afghanistan, the professor showed this photo slide of “four typical Mujahaddin fighting the Soviets.”

Brandon’s hand went up. “Yes, Cadet Wheeler?” the professor called on him. “Professor,” Brandon responded, “actually only two of them are Afghans – the man standing and the man in the middle, a commander named Moli Shakur. The man on the right is Congressman Dana Rohrabacher. The man on the left, who took Dana into Afghanistan, is my father. The picture was taken in November 1988.”

Shocked, the professor stammered, “Are you sure, Cadet Wheeler?” Brandon answered, “Yes, professor. I’ve known Dana all my life. Pictures like this are all over my father’s study. And I recognize my own father.” It was a pretty funny moment.

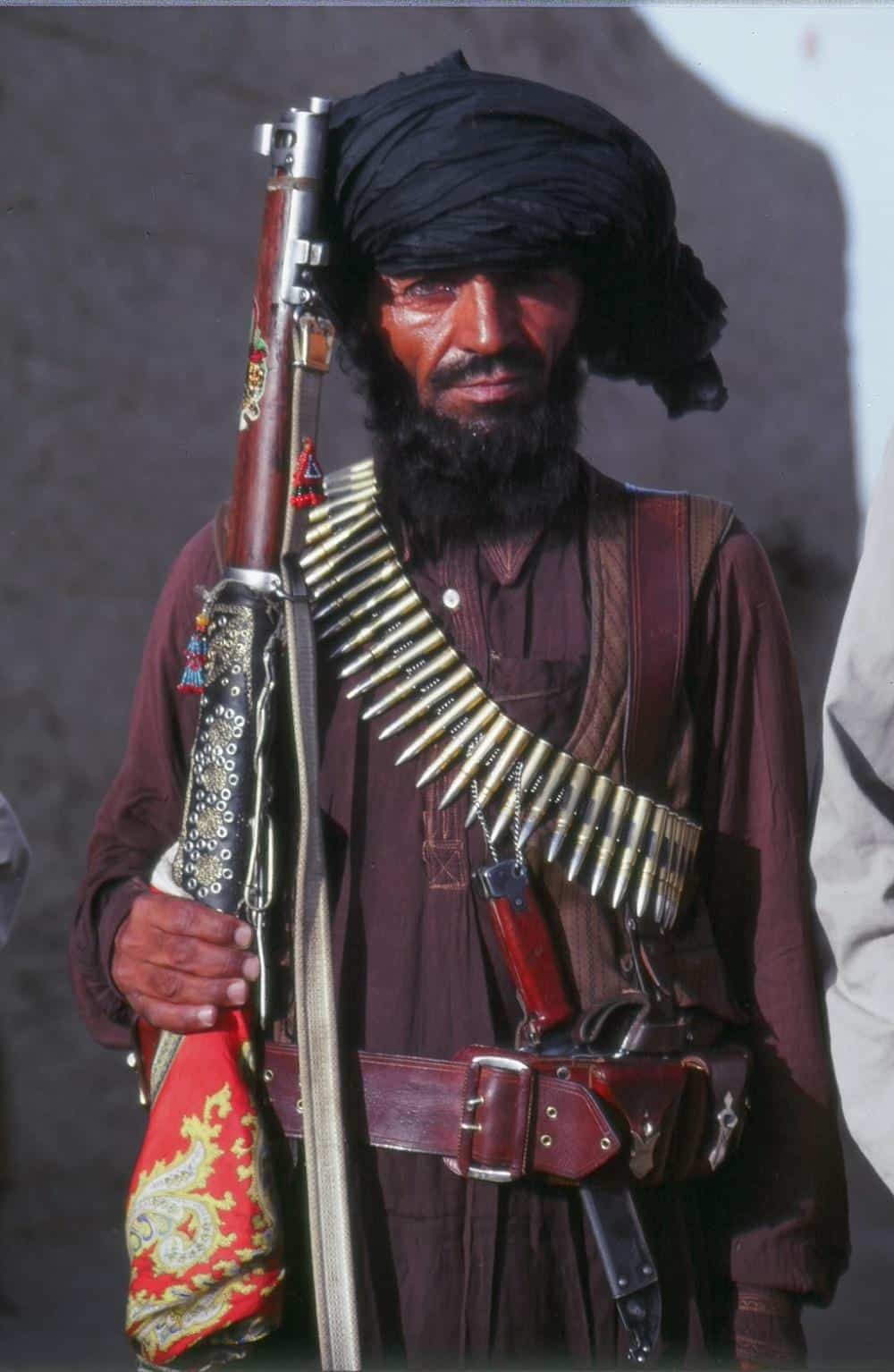

The Afghans are incredibly brave people. They had the guts to take on the Soviet Red Army face-up, armed initially with single-shot, bolt-action pre-WWI Lee Enfield carbines:

Photo by Jack Wheeler

Photo by Jack Wheeler

Nonetheless, as we’ll see, the Soviets had them fully defeated by summer of 1986, until President Reagan began supplying them with Stinger missiles. So let’s take a walk down the path of history to see how, for thousands of years, Afghanistan has been not the graveyard but The Doormat of Empires.

In 327 BC, Alexander the Great married a beautiful princess named Roxanne in Balkh, the capital of Bactria. She was the daughter of the King of Bactria, Oxyartes, and Alexander had just conquered his kingdom. Bactria is now northern Afghanistan – Alexander’s wife was Afghan.

Alexander subdued all of Afghanistan because, for over 200 years, it had been part of the Persian Empire he had vowed to conquer. The tribes of Afghanistan had been conquered by the founder of the Persian Empire, Cyrus (599-530 BC) in the 550s. After Alexander’s death in 323, Afghanistan was ruled by his general, Seleucus Nicator (358-281 BC) as part of the Greek Seleucid Empire.

Afghanistan’s second-largest city (after the capital Kabul) is Kandahar. The city was founded by Alexander in 330 BC and is, in fact, named after him, from the original Iskandaria (Alexandria – Iskander being the Persian pronunciation of Alexander’s name).

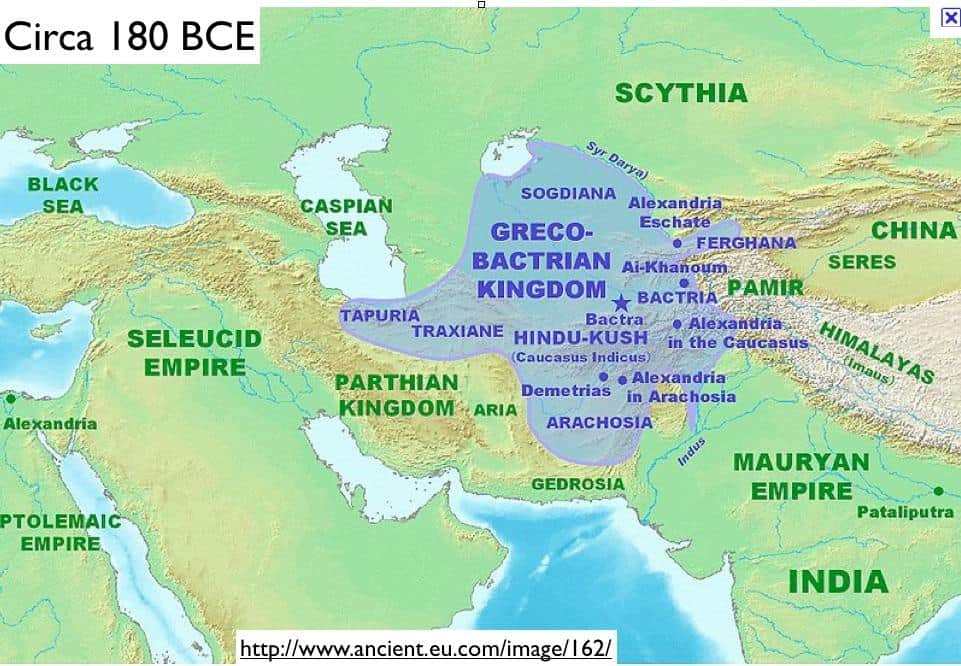

In 250 BC, the Greek governor of Bactria, Diodotus, saw his chance to break free of the Seleucids and established the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom. It expanded until it became known to the Romans as “the extremely prosperous Bactria of a thousand cities.” Under the rule of Demetrius Aniketos (Greek for “Invincible,” r. 200-180 BC), Greco-Bactria expanded to control present-day eastern Iran, Pakistan, and northwest India.

Under Menander Soter (Greek for “Savior,” r. 165-130 BC), the Greek kingdom expanded across northern India to what the Romans called the Menander Mons (Mountains of Menander), today’s Naga Hills that form the border between India and Burma. The religion and art of the entire region was a syncretism known as Greco-Buddhism.

Under Menander Soter (Greek for “Savior,” r. 165-130 BC), the Greek kingdom expanded across northern India to what the Romans called the Menander Mons (Mountains of Menander), today’s Naga Hills that form the border between India and Burma. The religion and art of the entire region was a syncretism known as Greco-Buddhism.

After a series of invasions by Hun-like nomadic peoples from China and Central Asia – the Yuezhi, Parthians, and Scythians – Greek rule of Afghanistan and northern India was reduced to a pocket of the Punjab and came to end under Strato II in 10 BC.

A branch of the Yuezhi called the Kushan came out on top and became so Hellenized in taking over Greek Bactria they adopted the Greek alphabet and Greco-Buddhism, worshipping Zeus and Herakles (Hercules) as a demigod.

The Kushan Empire expanded in the 1st century AD to control a vast swath of Central Asia and India. By the 3rd century, it was so huge that it fell apart – in the west to resurgent Persians known as the Sassanids (named after Sassan, grandfather of their founder Ardashir I, r. 206-241 AD).

The Sassanid Persians conquered what is now Afghanistan in the 240s, imposed their religion of Zoroastrianism upon the inhabitants, and incorporated it into a gigantic empire stretching from current Kazakhstan to Egypt. Their main focus, however, was war with Rome.

In 259, King Sharpur I captured Roman Emperor Valerian, and after killing or enslaving 70,000 Roman soldiers, flayed Valerian alive and kept his skin as a trophy.

Sassanid wars with Rome and Constantinople continued for 350 years, culminating in the Persian army of Khosrau II destroying Jerusalem in May, 614, slaughtering 90,000 Christians in cold blood and demolishing the Church of the Holy Sepulcher.

This prompted Emperor Heraclius in Constantinople to invade Persia in 621, wiping out Khosrau’s army at the Battle of Nineveh in December 627, and terminating the Sassanids.

Unfortunately for mankind, the resultant anarchy made it easy for wild tribes to pour out of Arabia and seize Jerusalem, the whole Middle East, and Persia in the name of Islam 20 years later.

The main city of western Afghanistan is Herat. It is dominated by a huge ancient fortress known as the Citadel of Alexander, Qala-e-Iskander, because it was originally built by Alexander in 329 BC. In 652 AD, fresh from sweeping across Sassanid Persia, an Arab army seized Herat. From there, Arabs and Moslemized Persians began forcing Islam upon the peoples and tribes of Afghanistan. It took them 300 years.

Then, in the 960s, a group of Turkic slaves, guards of the Arab-Persian rulers, seized control of the eastern Afghan city of Ghazni. The son of one of them, Mahmud of Ghazni (971-1030), conducted a horrific reign of Moslem pillage and slaughter, directed primarily at Buddhist-Hindu India, prompting historian Will Durant to comment: “The Mohammedan Conquest of India is probably the bloodiest story in history.”

The Ghaznavid horror was ended by a far greater one: The Mongol hordes of Genghis Khan (1162-1227). In 1220-21, Mongol butchers decimated much of Afghanistan, killing over a million people each in Herat and Balkh alone. A Chinese scribe with the Mongols registered surprise at seeing a cat in the ruins of Balkh – surprise that the Mongols left one single thing alive.

Afghanistan has never recovered to this day.

As the Mongol Empire dissolved in the late 1300s, a new one arose, led by yet another horrific conqueror, Tamerlane (Timur-e-Lang, 1336-1405). He was a Moslem Persian-speaking Mongol-Turk from near Samarkand in present-day Uzbekistan dedicated to massacring entire cities – Moslem or infidel, it didn’t matter to him.

In creating his Timurid Empire, his first invasion of Afghanistan was to wipe out a just-rebuilt Herat in 1370. Then he rebuilt it again from which to rule Afghanistan. By 1390, his subjugation of Afghanistan was complete.

100 years after Tamerlane, a new conqueror arose. Zahir ud-din Mohammed (1483-1531) was born in the Fergana Valley of current Uzbekistan. Dreaming of ruling an empire like his great-great-grandfather, Timur, he adopted the nickname of Babar (“Tiger” in Persian), recruited an army of Tajiks, crossed the Hindu Kush, and captured Kabul in 1504.

He then made a deal with the new Shah of Persia, Ismail I, to divide Afghanistan in half, Ismail getting the west, him the east. With his back covered, he launched his completion of Timur’s goal of conquering India.

With his victory over the Sultan of Delhi at the Battle of Panipat in 1526, the Mogul Empire was born. The Hindus of India called Babar “The Mogul,” The Mongol.

Afghanistan remained divided between the Persian and Mogul Empires for 200 years.

In the 1730s, a Turkmen bandit chief in northern Persia named Nadir figured out how to seize control of the disintegrating Persian Empire and declared himself Shah. Even before he consolidated his control over Persia, Nadir Shah (1688-1747) focused on subduing revolts in Afghanistan. He conquered Herat in 1730, then Kandahar and all of Afghanistan in 1738.

In Herat, Nadir Shah recruited Pushtun fighters of the local Abdali clan into his army. He was particularly taken with one of them, Ahmad Abdali, for his “young and handsome features,” who became his personal attendant or yasawal. Sufficiently pleased with the very personal services such a yasawal provided, Nadir promoted Ahmad – at age 16 – to commander of the Pushtun forces, and then later promised to make him King of Afghanistan.

Shortly thereafter, in 1747, Nadir Shah managed to get himself assassinated. Ahmad thereupon declared himself heir to Nadir’s Afghan dominions and his title padshah durr-i dawran, “king, pearl of the age.” He was 25 years old. The Abdalis changed their tribal name to Durrani, after Ahmad’s new title.

Thus, the country of Afghanistan was born. Ahmad Shah Durrani (as he is known to history, 1722-1773) and his army quickly gained control of Kandahar, Ghazni, and Kabul, took Herat from the Persians, and on to take Nishapur and Mashad in northeast Persia. Then he went for India, taking Punjab, Kashmir, and sacking the Mogul capital of Delhi in 1757. He declared a Jihad, Holy War, against the Hindus and slaughtered them wholesale.

His particular animus was towards Indian Sikhs, who constantly rebelled. He finally could not put them down, retreated back to Kandahar, and died at age 50. The Durrani Empire subsequently disintegrated. By the early 1800s, Afghanistan was fragmented into warring tribal units with the Durranis controlling only the Kabul Valley. So, in stepped the Brits.

The Great Game had begun. England had established their rule over India – the British Raj – and Russia was spreading its rule over Central Asia. Afghanistan was in between. By 1809, the Brits had a relationship with the last Durrani ruler, Shuja Shah in Kabul.

But Shuja Shah was overthrown and there was a chaotic Afghan Civil War that lasted until the leader of the Barakzai tribe, Dost Mohammed (1793-1863), managed to gain control of Kabul and Kandahar in the 1830s. When Dost became buds with the Russians, the Brits freaked and decided to try and put Shuja Shah – an exile in India for 30 years – back in power.

Big mistake. The First Anglo-Afghan War started well enough. The Brits took Kandahar, Gazni, then Kabul, Dost fled, and Shuja was installed as Afghan Emir in 1839. The Brits then tried to keep Shuja in power with a garrison of less than 5,000 troops. Dost’s son, Akbar Khan, began a guerrilla war against them.

By 1842, the Brits had to flee. Led by the amazingly incompetent General William Elphinstone, 4,500 soldiers (of whom less than 700 were European, the rest mostly Indian), along with 12,000 Indian servants and Afghans, retreated out of Kabul for Jalalabad. Of the 16,500, only one, army surgeon William Brydon, made it to Jalalabad alive.

This horrific annihilation of January 1842 is the source of the “Graveyard of Empires” myth. It was never repeated.

By September, a British army had marched back into Afghanistan and leveled Kabul to rubble. Akbar Khan was put to the sword. Dost Mohammed promised to do as he was told, which he did as Emir until his death in 1863.

When Sher Ali Khan, Dost’s son as Emir, began making nice with the Russians, the Brits tried to send a diplomatic mission to Kabul which Sher Ali stopped at gunpoint. This triggered the Second Anglo-Afghan War in September 1878. When Sher Ali found that Moscow would not help him against 40,000 Brit soldiers, he fled, and the Brits took Kabul and Kandahar without much problem.

By May of 1879, the new Emir, Mohammed Yaqub Khan, had signed a peace treaty with the Brits that granted Afghanistan sovereignty in exchange for England formally controlling all Afghan foreign affairs. When warlord revolts broke out in Ghazni, Herat, and Kandahar, the Brits handily snuffed them out. Then they replaced Yaqub with his cousin Abdur Rahman Khan. This second war was over by July 1880.

Abdur Rahman (1840-1901) was Dost’s grandson. He spent his emirship pacifying and putting down constant tribal revolts through his country. In 1893, he and British diplomat Mortimer Durrand negotiated the demarcation of the border between Afghanistan and British India.

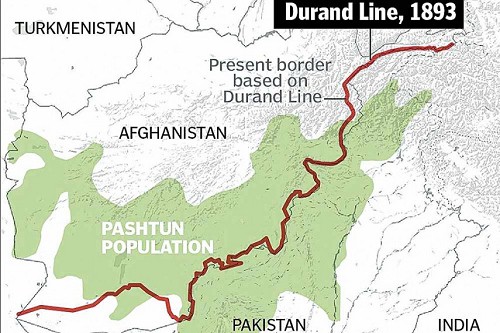

The resultant Durrand Line demarcates Afghanistan’s entire eastern border (now with Pakistan), 1,610 miles long, from China to Iran. It was confirmed by Afghan rulers by treaty in 1919, 1921, and 1930 – then rejected in 1949 after Pakistan became independent. Nonetheless, it remains the border today:

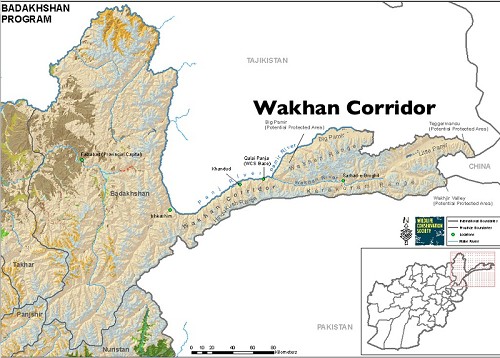

Mortimer Durrand then negotiated a treaty between Russia and England in 1895 to demarcate the Wakhan Corridor, which we went through last week in “The Pamir Knot.”

Mortimer Durrand then negotiated a treaty between Russia and England in 1895 to demarcate the Wakhan Corridor, which we went through last week in “The Pamir Knot.”

A panhandle 100 miles long and 10-40 miles wide stretching all the way to China, it was designed so that the British and Russian Empires would, however thinly, be separated by a strip of Afghanistan. The Wakhan now separates Tajikistan from Pakistan.

Rahman’s son, Habibullah (1872-1919), signed a Treaty of Friendship with Britain in 1905 and made a state visit to Buckingham Palace in 1907. He resisted every demand of the Ottoman Sultanate – the spiritual leader of Islam – to join World War I on Turkey and Germany’s side. He brought Western medicine to his country and made a number of educational and legal reforms.

Rahman’s son, Habibullah (1872-1919), signed a Treaty of Friendship with Britain in 1905 and made a state visit to Buckingham Palace in 1907. He resisted every demand of the Ottoman Sultanate – the spiritual leader of Islam – to join World War I on Turkey and Germany’s side. He brought Western medicine to his country and made a number of educational and legal reforms.

Tragically, he was assassinated in 1919, with heavy suspicion falling on his son, Amanullah – which was increased when Amanullah seized power and declared himself King of Afghanistan. As revolts mounted against him, he decided to distract them by declaring war on the infidel British. Thus, began the Third Anglo-Afghan War.

The Brits, however, were ill-equipped to fight it, with their units in India, and the Indian Army, hollowed out just after WWI.

Amanullah gathered thousands of Afghan tribesmen and, on May 3, 1919, invaded through the Khyber Pass. The Brits quickly rallied, and they, together with Gurkhas with bayonets, chased the Afghans back across the Khyber.

The fighting became dicey, and a lot of it took place in what is now ultimate Apache country, Waziristan. Yet, it took only a month before Amanullah sued for peace on June 3. Yes, the Third Anglo-Afghan War was won by the Brits in one month.

Amanullah lasted until 1929, when one too many revolts broke out, he abdicated, and his commanding general, Mohammed Nadir, went to India to ask for British troops. The Brits complied, and a British army marched to Kabul and installed Nadir as King. The main achievement of Nadir’s rule was to combat tribal revolts against him by setting the tribes against each other in race wars, primarily Pushtuns against Tajiks and Hazaras.

A Hazara teenager bumped him off in 1933. Then Afghanistan got lucky. Nadir Shah’s son, Mohammed Zahir Shah (1914-2007), became King at age 19 – and Afghanistan entered a golden age of peace that lasted 40 years.

I was lucky to be there during that golden age, back in ’63. When I was there in ’73 on my way from Europe to India, Zahir Shah’s cousin, Mohammed Daoud, had staged a coup with Soviet money. Soviet weapons flooded in, along with Soviet agents. The Afghan Communist Party exploded in growth – so much so it alarmed Daoud.

With good reason. Its leader, Hafizullah Amin, decided Daoud was more Afghan than Communist and staged a coup in April 1978, having Daoud and his family shot. All Afghanistan erupted in uncontrollable rebellion. In December 1979, Soviet leader, Leonid Brezhnev, ordered the Red Army to invade. KGB and Spetsnaz agents entered the presidential palace in Kabul on December 27, shot Amin, and installed another Communist, Babrak Karmal, as the Soviet puppet.

Karmal lasted until 1986, when the Soviets replaced him with the thuggish head of KHAD, the Afghan KGB, Mohammed Najibullah. As of August 1986, the Soviets had won. The Afghans were defeated. I saw it with my own eyes.

Then, on September 26, 1986, the first Stinger missiles were fired, shooting down two Soviet helicopters, and the war was back on. On February 15, 1989, the Soviets finished their retreat. It was Stinger missiles from Ronald Reagan that defeated the Soviets, not the invincible unconquerable Afghans who make a graveyard of every army that ever attempted to conquer them in all of human history.

As you’ve now seen, this is rubbish. So how come the greatest military force on the planet – America’s – remains stuck in Afghan quicksand? Primarily because of the perverse incompetence of the CIA and U.S. State Department in refusing to recognize what really is the problem.

That problem is the ISI, the Pakistan CIA, Inter-Services Intelligence. Ragingly radical Islamist, it’s the sponsor of the Taliban. No ISI, no Taliban. Langley and Foggy Bottom are completely aware of this, yet they resolutely refuse to do what it takes to get rid of the ISI.

Further, State has an anaphylactic allergy to changing a country’s status quo, particularly its borders, and especially recognizing its existence as a failed state that can’t be resuscitated.

Afghanistan has a 19th-century raison d’état – it was created quite specifically and for no other reason than to be a buffer state between the British Empire in India and the Russian Empire in Central Asia.

That rationale shifted into a 20th-century context of the Cold War between America and the Soviet Union – but with the breakup of the Soviet Union, the rationale has, in the 21st century, been rendered totally obsolete.

The world is a better place, clearly and objectively, because the Soviet Union no longer exists. The world will be a better place if Afghanistan no longer exists. Just as what ended the Cold War was the disintegration of the “Union” of Soviet Socialist Republics, so the War in Afghanistan can only end with Afghanistan’s disintegration.

The solution is not a futile effort of “nation-building” – that effort is doomed to fail – it is nation-building’s opposite: get rid of the problem by getting rid of the country. It’s a salvage operation – carve the wreck up and parcel it out to its neighbors.

Which means we first have to look at the neighbors. The problem of Afghanistan cannot be solved in isolation, but within its geopolitical context. Those neighbors are Iran, Pakistan, Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, and Turkmenistan. You can’t really count China’s tiny roadless border at the tip of the Wakhan Corridor.

The Brits created Afghanistan in the 19th century as a Pushtun Empire – Pushtuns ruling the other ethnic peoples in the country. Indeed, “Afghan” is a Pushtun word, another name Pushtuns apply to themselves.

Today, Pushtuns are way less than half of the population – 14 million out of 35 million, or 40% – yet they continue to dominate both the government and the Taliban. The Taliban is essentially a Pushtun movement.

Yet the Durrand Line divides “Pushtunistan” so that there are more than twice as many Pushtuns in Pakistan – 32 million – than there are in Afghanistan. The Afghan Pushtuns have always dreamed of being united with their ethnic brethren right across the border in Pakistan – so let Pakistan absorb them.

Tajiks comprise a full 33% of Afghanistan’s population, 11.5 million – way more than Tajiks in Tajikistan (7.5 million out of 8.5 million total. They live in a wide swath of northern Afghanistan with 750 miles of border with Tajikistan reaching west to the border with Iran). They’d love to join Tajikistan, and they’d be welcomed.

Uzbekistan’s Afghan border only runs 85 miles. To the south of it lives a bit more than 2.5 million Uzbeks. The region is run by a warlord named Abdul Rashid Dostum, who’s also Afghanistan’s current Vice-President. A deal with him to retain control of his region as part of Uzbekistan is doable.

Even though Turkmenistan’s Afghan border runs about 450 miles, it’s mostly uninhabited wasteland. Less than a half-million or about 400,000 Turkmen live in the region. The leader of Turkmenistan is an odd duck dictator, Gurbanguly Berdimuhamadov. Nonetheless, no need to antagonize him by excluding him – he’ll jump at the deal.

Next is Iran. Afghanistan’s border with Iran runs 580 miles – but there are almost no Persians in Afghanistan. Western Afghanistan is mostly Tajik, as is Herat, the largest city in the region. So there is no reason to carve up Afghanistan for Iran’s behalf.

Then there’s central Afghanistan, a region called the Hazarajat because it’s peopled by descendants of Genghis Khan’s Mongols called Hazaras. They are Shia Moslem and number (together with Sunni Hazaras called Aimaqs) about 4 million. Since they bear an extreme antipathy towards the Taliban and Pushtuns in general, most likely they would opt to join Tajikistan.

In sum: The basic problem is the obsolescence of Afghanistan as a nation-state. The solution is: northern and western Afghanistan to Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, and Turkmenistan; eastern and southern Afghanistan to Pakistan.

And get rid of Pakistan’s ISI.

A few years ago, when Adm. Mike Mullen was chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, he was worried about “the Tajik-Pashtun divide that has been so strong.” In an interview, Admiral Mullen said, “It has the potential to really tear this country apart. That’s not what we are going to permit.”

Trapped in a 19th-century thought-box, Mullen, like almost everyone else at Langley, State, and elsewhere, doesn’t grasp that it’s exactly what we should not only permit, but should work to achieve as the solution to this war. For what could be called the Dissolution Solution to Afghanistan.

It’s time to end the necessity of putting American and NATO soldiers in harm’s way there. It’s time to ask, why should there be an Afghanistan?

Jack Wheeler is the founder of Wheeler Expeditions

©2019 Jack Wheeler – republished with permission

Like Our Articles?

Then make sure to check out our Bookstore... we have titles packed full of premium offshore intel. Instant Download - Print off for your private library before the government demands we take these down!